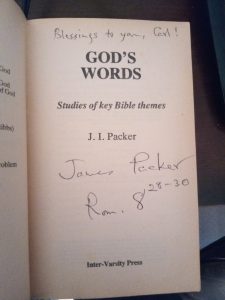

I can clearly remember the moment I first heard the name of J. I. Packer. It was September 27, 1985, the day before I went up to Cambridge as an undergraduate, and the local Baptist minister, Leslie Beard, gave me a copy of God’s Words as a going-away present. It’s perhaps not the most well-known, or even the best, of Packer’s many books. But it changed my life and even today sits on a shelf just a few feet away from where I’m writing, nestled between a volume of Chaucer and the poems of Wordsworth, among the books I most value.

The book changed my life because it explained the importance of God’s grace to me in a way that I hadn’t seen before. Through careful chapters on key biblical themes, Packer laid out the glories of the faith in a way that was both accessible and also clearly learned. I even remember running across the main court of my college late one night to tell a friend that the book had turned me into a Calvinist—though at the time I did not know the word, merely the basic doctrines. Later, reading Packer introduced me to the Puritans and then the works of John Owen, one of my major academic interests.

Strange to tell, it’s probably another one of his least regarded books, Keep in Step with the Spirit, which helped me most. Written in the heat of the controversy about charismatic gifts, it was hammered by both parties in that debate. Cessationists thought it too concessive to the continuationists, continuationists too concessive to the cessationists. As someone brought to Christ through the witness of a charismatic Anglican friend, I liked it because its charitable tone—the very thing that seemed to upset many readers—showed me how I could reject the charismatic movement without having to reject my friends.

Debts of honor are important. Gratitude is a virtue.

Evangelicalism Didn’t Deserve Packer

Intellectually and spiritually, therefore, I cannot quantify his influence on my life, and yet there were times when he became a more ambiguous figure to me. Despite my debt to him, I was also influenced by the British evangelical world that had emerged after the painful splits between Anglicans and non-conformists in the period between 1966 and 1970, beginning with Martyn Lloyd-Jones’s public disagreement with John Stott and finalized, in a sense, by his break with Packer over the latter’s involvement in the book Growing into Union. For many years, I took the Lloyd-Jones line on these matters, looking with some suspicion on Anglicanism as a whole and its British evangelical leadership in particular. And when more than 20 years later Packer signed the Evangelicals and Catholics Together statement and experienced a fresh round of anathemas in North America, history in a sense repeated itself. And while I disagree with his action in that regard, there is no doubt that the subsequent marginalizing of Packer in the American Reformed world was a loss to the latter. His was a learned and gracious voice, and he deserved better than he received.

Intellectually and spiritually, therefore, I cannot quantify his influence on my life, and yet there were times when he became a more ambiguous figure to me. Despite my debt to him, I was also influenced by the British evangelical world that had emerged after the painful splits between Anglicans and non-conformists in the period between 1966 and 1970, beginning with Martyn Lloyd-Jones’s public disagreement with John Stott and finalized, in a sense, by his break with Packer over the latter’s involvement in the book Growing into Union. For many years, I took the Lloyd-Jones line on these matters, looking with some suspicion on Anglicanism as a whole and its British evangelical leadership in particular. And when more than 20 years later Packer signed the Evangelicals and Catholics Together statement and experienced a fresh round of anathemas in North America, history in a sense repeated itself. And while I disagree with his action in that regard, there is no doubt that the subsequent marginalizing of Packer in the American Reformed world was a loss to the latter. His was a learned and gracious voice, and he deserved better than he received.

But we all grow older. And hopefully we grow a little wiser. As the years have passed it is clear that it was Packer who aged with personal integrity and charm while many of his critics, for all their “orthodoxy,” weren’t so strong on the matters of humility, respect for others, and true love for the church rather than their own status. The battles of the ’60s and ’70s in British evangelicalism fostered little but acrimony and, in the end, the Packer vision of a more thoughtful, less rhetorically divisive movement has emerged stronger.

The modest Packer was never a good fit for the often brash, swaggering world of American evangelicalism.

And in North America, theological orthodoxy can sit comfortably with the aesthetics of power and the personal ambitions and corruptions of those in leadership. Packer may have erred on the side of charity in his ecumenical dealings. But he reached the end of the race with humility and integrity, too rare in evangelical leaders—though in a sense “leader” might well be the wrong word. He never became a powerbroker. He seems to have lacked all personal ambition. He didn’t bother to build his brand. He didn’t trumpet his own greatness from Twitter. He simply wrote good, helpful books, gave solid lectures, and steadily preached the Bible.

Kind Man to the End

Packer may have erred on the side of charity in his ecumenical dealings. But he reached the end of the race with humility and integrity.

I only met him once. We spent the day together in 2012. Though some 40 years older than me, we both grew up as Gloucestershire grammar school boys. Only a grammar school boy understands what an instant bond that gives. We talked about our home county. We discussed John Owen and Richard Baxter. He took me to his favorite jazz-themed restaurant for lunch. He even briefly lost his temper with me when I had the temerity to suggest that he was the great Presbyterian leader who never was. “I am an Anglican by conviction!” he said, as he banged the table with his fist.

As we parted, Packer did me one last kindness: he signed my battered old copy of God’s Words. Yes, I had taken it with me. Yes, it’s now my one Protestant relic. And yes, as I look at it on my shelf, it’s a treasured reminder of a truly great man who has now finished the race with true greatness.

Shalom, Dr. Packer, shalom.

Read More

The Gospel Coalition