In the days after George Floyd’s death, at least 140 cities lit up with protests. Streets shut down in Memphis and Louisville; in Los Angeles protesters blocked the freeway. Demonstrators smashed windows and sprayed graffiti in Atlanta and New York City. Protesters were shot in Detroit and Austin; officers were killed in St. Louis and Las Vegas. The National Guard was summoned in 21 states.

In Montgomery, Alabama, pastor Jay Wolf got word that activists across the south were coming to his city—home of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr.’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church—to set fire to the federal courthouse.

“It was just overwhelming,” he said. First Baptist Church sits two blocks from the courthouse.

Wolf didn’t know exactly what to do. But he knew who to ask. He began trading phone calls with his pastor friends. He’s got a lot of them—white, Black, charismatic, Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist.

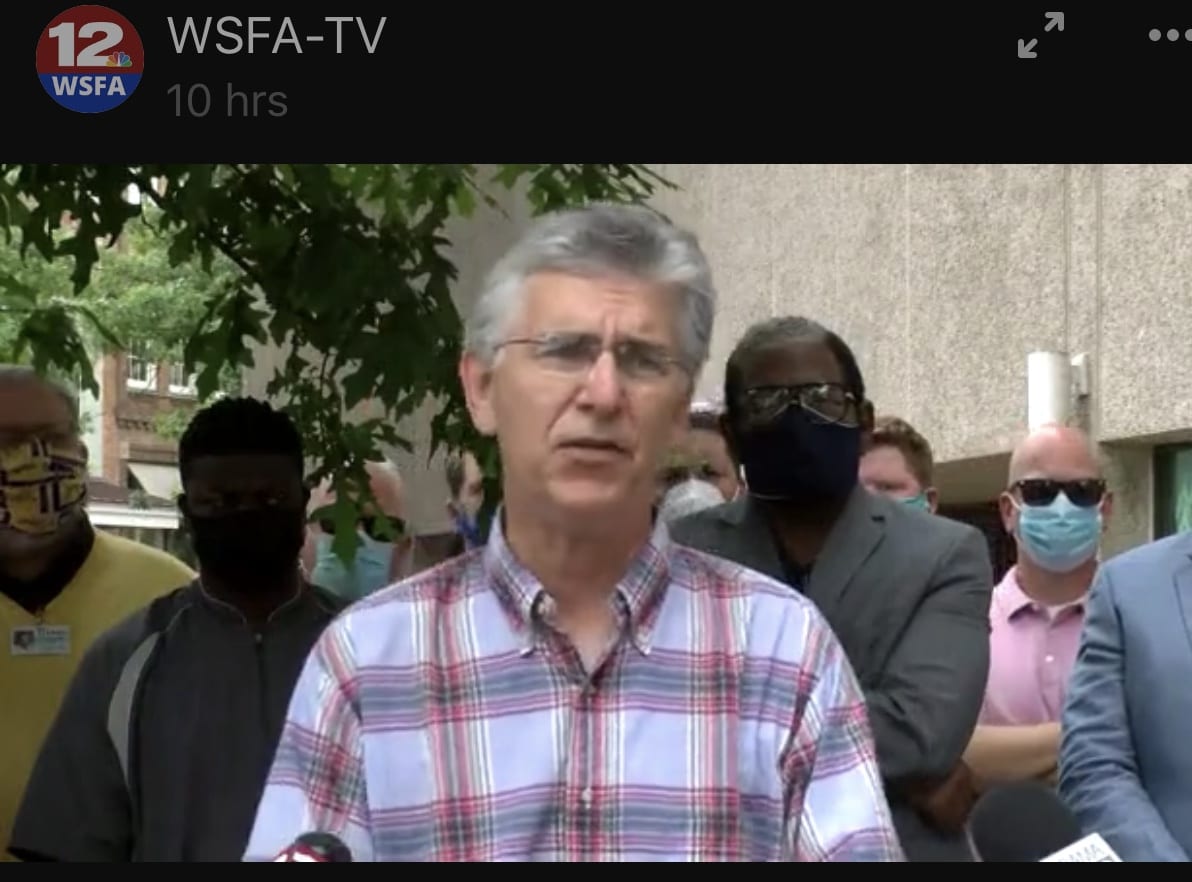

One of them organized a news conference that drew about 100 people—including at least two news outlets—and 100,000 views online. You are heard, they told protesters. God is a God of justice. Jesus died for all our sins. Let’s protest peacefully. Let’s not hurt the city we love. Real change comes from God.

It seemed to work. In Montgomery, police didn’t brandish weapons. Protesters largely dispersed at the 10 p.m. curfew. A statue of Robert E. Lee was pulled down outside a high school, but nobody showed up to protest city hall and nobody broke past the barricades to reach the capitol building. Glass wasn’t shattered; fires weren’t set.

Reporters wrote headlines such as “Montgomery protesters remain largely peaceful in comparison to other large cities” and “Constructive not destructive: No confrontation, no violence at Montgomery protests. Why?”

It would be stretching to say that Montgomery’s protests stayed peaceful because of that gathering. The city also has Steven Reed, its first African American mayor, and Ernest Finley, its African American police chief. Both are Christians, and both worked to respect protesters and to protect property.

But at least some credit is due to that multiethnic group of pastors, who have been meeting for the past 25 years to pray for the city. They call themselves the John 17 group after Jesus’s prayer for unity in John 17:21. Their regular meetings have led to prayer walks, pulpit swaps, and joint ministries. And it’s led to a trading of phone numbers, so when the time comes, it’s easy to get in touch.

“The Lord used it,” Wolf said. And he’s using it still—this past summer, the original pastors invited younger ministers to a series of meetings so they too could talk and pray and trade phone numbers.

“The Bible says we’re ministers of reconciliation,” said Courtney Meadows, the 27-year-old pastor of Hutchinson Missionary Baptist Church. “As we do that at the micro level, we can see it manifest at the macro level.”

Privilege and Prejudice

Wolf grew up on a Texas ranch during the 1960s, in “a home of privilege and plenty and prejudice.” He remembers the railroad tracks that separated the white kids from the Hispanic immigrants, and a rock fight between the white kids and the black kids. (“It was a pinnacle reflection of ‘inherent sin.”’)

When he was 13, a teacher “with the glow of God all over her” shared the gospel with him.

At least some credit is due to that multiethnic group of pastors, who have been meeting for the past 25 years to pray for the city.

“I’m digging into the Word, and the Word is digging into me,” he said. “I remember reading 1 John 4: ‘Beloved, let us love one another, because love is from God. How can you say you love God when you hate your brother?’ The Lord really spoke to my heart about prejudging people.” That was confirmed in a Jesus Movement revival at his high school, with kids of all skin colors coming to Christ.

More than two decades and two educational degrees later, Wolf was called to First Baptist in Montgomery. He loved the location—smack in the middle of the African American west and Caucasian east side of town. And he was fascinated by the history: four blocks away, the telegraph was sent advising general P. T. Beauregard to fire on Fort Sumter.

A previous pastor, Basil Manley, helped start The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. (He also prayed at the inauguration of Jefferson Davis.) Half a mile away sits Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr. pastored for more than five years. The Selma-to-Montgomery marches ended at the state capitol, less than a mile from First Baptist.

Wolf started by preaching exegetically through the Bible, sounding the note of racial inclusion whenever he could. “I called the congregation not to conform to culture, but to Christ.”

After a while, he met a charismatic pastor named Carmen Falcione, who would “walk up and down the streets, praying for revival and reconciliation, for government leaders and for pastors,” Wolf said. The two didn’t agree on everything, but they did agree on the centrality of the lordship of Christ, the need for salvation, and Montgomery’s problems with race.

Falcione loved unity in the body of Christ (he’d started a local ministry for it called The Gathering), and he was connected with the local radio station. “We’d announce that we [local pastors] were meeting in a room at the radio station, or at one of the churches, to have a nice meal and connect,” Wolf said. “Pastors just started coming—a mix of black and white, a mix of denominations.”

Ken Austin was pastoring in Montgomery in the early 1990s when a pastor friend told him he was taking him to lunch.

“We ended up at a church building with a group of men,” Austin said. “I was blown away. I saw the chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court on his knees praying to God. Men throughout the city were coming together praying, crying out to God, and it blew my mind. I’ve been part of it ever since.”

Fruit from John 17

At the gatherings, soon dubbed John 17, the pastors didn’t talk about doctrines or argue over ecclesiology. They didn’t do a Bible study. They weren’t even focused on unity as a goal. Instead, they prayed for an hour for Montgomery—for the schools, the government, the community.

“It was about starting revival and creating awakening,” Wolf said. “And the wind of the Spirit caught the sail.”

“We didn’t allow our differences to become significant,” Austin said. “We talked to God, not each other. You could feel the Spirit and the love driving up. . . . Each meeting, I couldn’t wait to get there.”

Billy Irvin, director of ministry relations at the local Christian radio station, remembers his first meeting. “In the middle of the week, different pastors from different denominations and different-sized churches were coming together to pray,” he said. “It was really neat. . . . You’d hear them share about their ministry and you could tell by their prayers they knew what each other’s needs were.”

He was surprised to see so many pastors had managed to show up. “One of the biggest challenges with a pastor is getting their time,” he said. Wolf kept the time blocked off on his calendar. Another pastor changed his weekly staff meeting so he could make it.

After praying, the pastors got to know each other—How are your kids doing? What’s going on at your church?—over a meal.

“We make this so complicated, but it’s forgiveness and fellowship,” Wolf said. “What did the early church do? They ate meals together. It sounds simplistic, but I think it is.”

Within a few years, the group had grown to 70, and was given a physical space—sponsored by a local law firm—it could use anytime. “We called it a prayer room,” Austin said. “We were in and out of that place. It never closed. We were always crying out to God.”

That wasn’t all they were doing. As they got to know each other, they started to get ideas.

“In the early 1990s, we started a tutoring program for at-risk kids in George Washington Carver Richardson’s [Hutchison Missionary Baptist] church,” Wolf said. They fed, tutored, and loved more than 2,000 kids. (“I can show you tutors who paid for their child’s college education.”) The two churches also cohosted an evangelistic event with Florida State football coach Bobby Bowden at the civic center. (“We saw all these people come to the Lord.”)

For the anniversary of the 1955 bus boycott, the John 17 group created the ONE Movement, which distributed black-and-white wristbands and crosses to symbolize racial reconciliation. The same year, Alabama Baptist State Convention messengers voted without debate to use the bus boycott anniversary to “foster unity among the African American and white churches,” to seek ways “to connect our congregations with African American congregations in joint evangelism efforts,” and “to destroy barriers of racism and build bridges of racial reconciliation to unify the body of Christ.”

Other pastors were scheduling pulpit swaps and sending volunteers to each other’s ministries. Sometimes Austin would load the pastors onto a bus and drive around town, and they’d pray for different communities. The group’s pastors were well-known enough that the police chief called them after Ferguson to ask for prayer that Montgomery would stay peaceful. (They did, and it did.)

But slowly, over the years, the John 17 group began meeting less often. Schedules were busy, and anyway, they knew each other now. Phone calls and partnerships were happening on their own.

Then came 2020.

John 17 in 2020

For some in Montgomery, the drama of 2020 started back in 2019. In January, a 16-year-old boy was shot while he lay sleeping in his bed. Austin, who volunteers as a chaplain with the police department, was called out. When he got there, he recognized the whole family, including the slain Jaylan Saunders. He was their pastor.

Furious, Austin “came home and cried and prayed and threw things.” Then he picked up the phone and sent a text. The next day, 60 pastors and community leaders gathered at his church. Within a week, they’d organized a community march to protest the violence and pray for peace.

Austin, who also runs a ministry called the Mercy House, kept organizing. Every month, he picked a different community, contacted the churches and schools to see if he could pray in their parking lots, and alerted the police to the route he wanted. Then on Saturday a crowd would gather—pastors and church members from across the city—to spend an hour walking through a neighborhood, talking to one another, and stopping in seven different locations to pray. It was like John 17 for all of Montgomery’s Christians.

“People in churches who didn’t know each other now had a chance to build relationships that make the city better,” Austin said. “The connections we make—tutoring inside the schools, churches partnering with other churches—those things happen just by walking together.”

When COVID hit, the marches moved online, and Austin started worrying about something else. In early July, he got a call from a child who didn’t have any food in his home. By now an experienced networker, Austin began pulling nonprofits, government officials, and his John 17 group onto a conference call.

“We had four people on the first call,” Mercy House director of operations Madison Darling said. Two days later, they did another call with 28 people. Eventually, they’d host more than 250 people on a daily 7 a.m. call that offered prayer from a pastor, COVID news from the government, and needs from the nonprofits.

“God really blessed it,” Austin said. “The chief of police would report on what to do for public safety. The food-bank president would give information on how we can best get food out. The school board superintendent might say how amazing it was that God used that to reach a community in its time of need. It was amazing.”

It was also noncontroversial. Black or white, everyone can get behind a prayer walk or handing out meals to hungry children. Things got trickier toward the end of May, when George Floyd was stopped by Minneapolis police.

George Floyd

The post–George Floyd press conference came together more like a teenage girl sleepover than a professional event.

“What happened was Jere Beasley (a prominent local lawyer) called me,” Austin remembers. “He said, ‘Pastor Austin, the elders of this city need to come together.’ So I called John Ed Mathison (retired pastor of Frazer United Methodist Church). We said, ‘Let’s get Jay Wolf (pastor of First Baptist Church).’ Because he’d just lost his mother-in-law, he was in Mississippi. We called him and Claude McRoberts (pastor of Trinity Presbyterian Church). Then I called Kyle Searcy (pastor of Fresh Anointing House of Worship) and Ed Nettles (pastor of Freewill Missionary Baptist Church).”

The pastors did more than call for peace in the streets—Mathison apologized “for many of us as whites—we’ve not listened well.” Searcy explained how Floyd’s death “angered us; it frustrated us. . . . Something like that should never happen.” Wolf spoke about his childhood prejudice and the change Jesus had made. “God is calling us to . . . find hurting and disenfranchised people, and not hurt them but help them, care about them, love them. That is our most basic core calling as a human being and as a follower of Jesus Christ.”

They scheduled another time for public prayer—this one with police officers. But the pastors could see a problem. The John 17 group had grown so relaxed that they’d stopped formal meetings. Although that was fine for a while, things were changing: Mathison had been retired since 2008, and Nettles and Wolf were slated to retire in 2020. But clearly, the need for pastors to together address the needs of the city wasn’t going away.

The older pastors “felt strongly God was calling them to speak to younger pastors,” Austin said. Initially, “I fought them on it, because I didn’t have time for that.” Along with pastoring, Austin drives kids daily to a local Christian school, runs Mercy House, serves as a chaplain with the police department, and organizes the prayer walks.

“I don’t have an assistant pastor,” he told them. “I can’t devote myself to doing that.”

But the retired guys voted him down and went in search of the next generation.

Next Generation

“It’s amazing what they’ve been able to do,” Austin said. Each older pastor invited eight to 10 younger pastors to a series of meetings and told them to bring their pastor friends. The format—an hour of prayer, followed by talking over a meal—was much the same. So was the need for communication.

“We talked through what was happening in the church, and what we were hearing in the community,” said Meadows, who came on as pastor at Hutchison Baptist Church in March 2020. “It was very powerful.”

It could also be heated, as the pastors discussed how to teach their congregations about biblical justice—justice that aims not for revenge but reconciliation.

“You have to have the John Ed Mathisons and Jay Wolfs and Kyle Searcys who will help bring that temperature down and moderate,” 36-year-old pastor Chris Montgomery said. “Something can get said that strikes a chord in somebody and it can get very tense. But also people will admit that while a certain situation hasn’t been their experience, another has been—and you can find common ground there.”

The pastors also learned about each other’s projects, from feeding the hungry to registering voters to fixing up houses and renting them to low-income families. As they started to learn each other’s names and faces and phone numbers, it felt like a mantle passed down from fathers to sons, Meadows said.

“I’ve never seen collegiality among clergy in a city like I have in Montgomery,” said Montgomery, who took over at Frazer United Methodist Church in July. Because of COVID, “I was meeting more pastors in the city than I was members of my own congregation.”

Lynn Bright began working with the John 17 group when her husband Bobby was mayor from 1999 to 2008. “It would be my prayer that every city would have a John 17 group or something similar,” she said. “Believers who have a common purpose based in Scripture can do so much.”

Already, the pastors have rallied behind Grace Pointe Church youth pastor Matt Renahan, who had a vision for regular prayer nights. They were able to come up with a reconciliation letter generic enough that everyone could sign it. And Frazer has added praying for other congregations to the beginning of its services.

“My dream would be that we’d continue to build on the amazing legacy that’s already here,” said Montgomery. “It’s natural for us to silo off. . . . The nature of evil is that it separates us, from God and from others and from ourselves. But when you’re intentional about keeping Christ in the middle of what you’re doing—all for his glory—then it’s amazing what can be accomplished.”

Read More

The Gospel Coalition