“Lift Every Voice and Sing”

It didn’t start out as the Black National Anthem which was sung last year before a number of National Football League games, as well as sung by Alicia Keys in this month’s Super Bowl game. It was merely a lovely piece of poetry, written and set to music by two African-American brothers from Jacksonville, Florida at the turn of the previous century.

It was to be “sung by a chorus of five hundred colored school children” in 1900 to celebrate the occasion of Abraham Lincoln’s 91st birthday and the auspicious visit of Booker T. Washington to the Stanton School, the first and largest public school for African-American students in Florida. That was the way this famous song was described by its author James Weldon Johnson in his wonderful collected works of poetry. He explains that over time it became “popularly known as the Negro National Hymn” simply because students from that day went to other schools and taught the song to classmates. Others became teachers themselves and taught it to their students throughout the nation over the decades. Johnson recounts for his readers that “the lines of this song repay me in an elation, almost of exquisite anguish, whenever I hear them sung by Negro children.” It might not be well known to all Americans, but its tune and beginning lines are written in the souls and minds of millions of black Americans.

The song was later included in a book of poetry published by Johnson entitled Saint Peter Relates an Incident of the Resurrection Day. It also appeared in countless hymnals, sung by congregations across the nation.

The beautiful anthem consists of three stanzas. The first pregnant with Liberty, faith, and a resounding and determinate hope in a better tomorrow…

Lift every voice and sing

Till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us.

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.

The second is darker, speaking of the tremendous pain of a whole people. Of slavery, flooding tears, mistreatment, and unjust death.

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

Out from the gloomy past,

Till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

The third speaks of God who knows the unspeakable torment and suffering of every black man, woman, and child brought in chains to a land that might one day truly be theirs as well.

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

Thou who hast brought us thus far on the way;

Thou who hast by Thy might

Led us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee,

Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee;

Shadowed beneath Thy hand,

May we forever stand.

True to our God,

True to our native land.

It is not a revolutionary song. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is a conserving proclamation of hope and justice which is the poem’s great power and appeal. It calls to envision and fight for original ideals: Of liberty, of freedom, of equal opportunity and dignity for all people regardless of skin color. It speaks of perseverance, of determination, of faith in God, and of true patriotism “true to our native land.” That land which is best suited and capable of raising the fortunes of everyone. You can watch its recent performance by members of the United States Army Field Band.

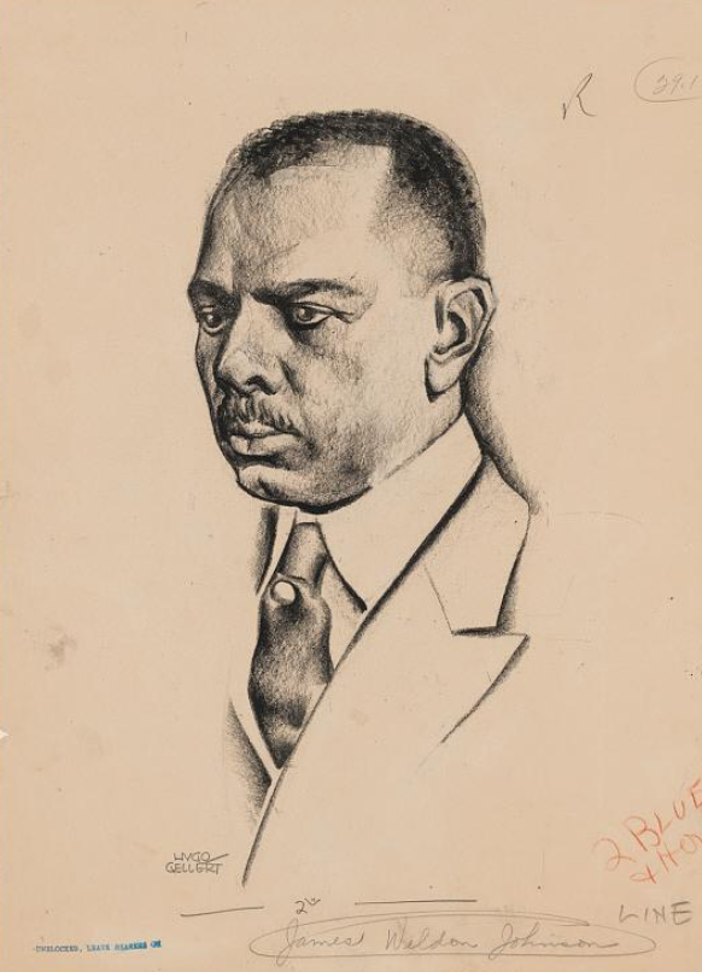

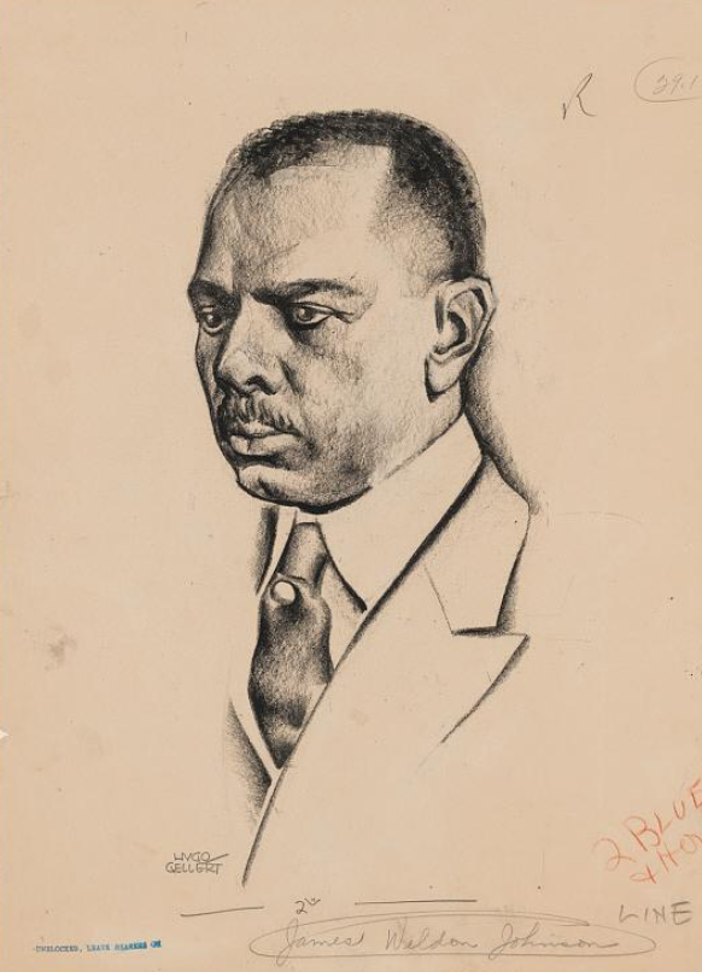

One cannot also fully appreciate the virtue of this anthemic hymn without appreciating the story of its author. James Weldon Johnson was a man of remarkable accomplishments, boundless creativity, and matchless conviction. Primarily educated by his mother, he attended Atlanta University at the age of 16. His father was a preacher and headwaiter at an exclusive Florida resort. He became a leader in education, serving as the principal of the historic Stanton School, one of the first and largest schools founded in the United States for black students. In 1895, Johnson founded his own daily newspaper, the Daily American and was also the first African-American to be admitted to the Florida bar.

In 1901, Johnson was elected president of the Florida State Teacher’s Association and nearly lynched that same year in a Jacksonville public park. Soon after, he moved north to New York City for safety, where he attended graduate school at Columbia University and wrote songs for Teddy Roosevelt’s presidential campaign. He also became the editorial page of The New York Age, one of the most prominent black newspapers of its day. He also became the first black professor to teach at New York University. He also published several literary works that enjoyed critical acclaim and cultural influence.

Johnson became an early leader in the American civil rights movement, serving as national president of the Colored Republican Club and the first executive secretary for the NAACP, having founded many new local chapters around the country. He was also a leader in the Harlem Renaissance, an intellectual and cultural movement of African-American art, music, literature, theater, and politics. He also served President Teddy Roosevelt as his consul to Venezuela and Nicaragua for nearly a decade.

The U.S. Postal Service issued an official commemorative stamp celebrating Johnson and his famous song on February 2, 1988. Johnson was a man of profound Christian faith and deep personal conviction. He had not the slightest doubt who he was and to Whom he belonged. In the twilight of his life, he explained how he endeavored to keep this “pledge to myself…through the greater part of my life is:”

I will not allow one prejudiced person or one million or one hundred million to blight my life.

I will not let prejudice or any of its attendant humiliations and injustices bear me down to spiritual defeat.

My inner life is mine, and I shall defend and maintain its integrity against all the powers of hell.

— James Weldon Johnson

You can listen to very early recordings of Johnson reading a number of his poems from the University of Pennsylvania sound archive. And here is a special performance of Ray Charles and the Raelettes singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing” on The Dick Cavett Show in 1972:

This Black National Anthem is an important proclamation for all Americans to know and take to heart, especially in these present and trying times of unrest.

Photo from Wikipedia

The post The Conservative Origins of the Black National Anthem appeared first on Daily Citizen.

Read More

Daily Citizen