Augustine’s Confessions is a strange book. Like many ancient books, its style and tone are so unfamiliar to the modern reader. Yet it was also strange for Augustine’s contemporaries because its genre and structure are so unusual to most first-time readers. Despite being unfamiliar and unusual, the Confessions has surprised centuries of readers by naming and explaining concerns and questions they too have felt yet may not know how to articulate. His concerns are so common that they are always contemporary, and his answers are so ancient that they have endured. And so the Confessions has continued to baffle and satisfy generations of readers.

Before we consider reasons to read Confessions, we must first address three interrelated puzzles that perplex many first-time readers: the puzzles of audience, genre, and structure.

What Are the Confessions?

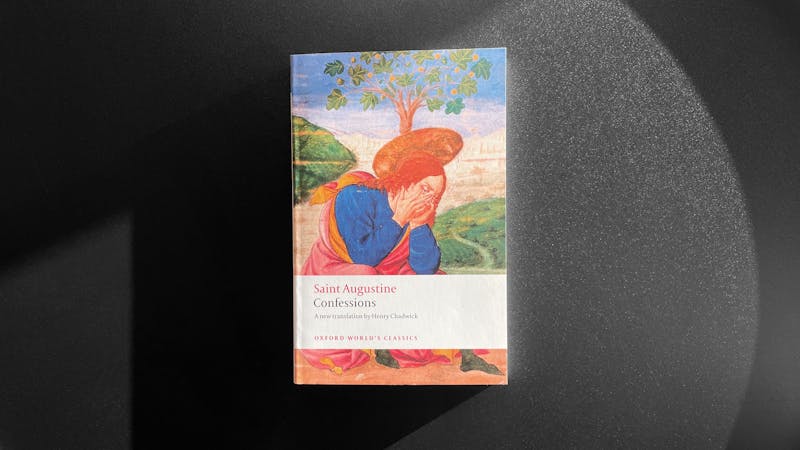

Let’s imagine you have the book in front of you now. (Better yet, go grab it off your shelf if you have it, or click on the preview feature for this translation.)

Audience Puzzle

You flip to the first page, and you notice immediately that Augustine is not talking to you at all. Rather, like the psalmists, Augustine speaks directly to God, confessing not just his sin but also his praise: “You are great, Lord, and highly to be praised” (1.1.1). He never directly addresses his human audience. You realize this book is a three-hundred-page prayer to God designed for you to overhear.

Genre Puzzle

You quickly discover too that while scenes from Augustine’s past dot the landscape of the book, telling a linear, chronological narrative of his life is not the author’s main aim. Instead, he narrates past scenes in order to analyze them, gazing at the darkness of past sin only enough to see the brightness of Christ’s mercy (2.1.1). Similar to Old Testament prophetic books and also the Gospels, Confessions is a mixed-genre text, incorporating autobiographical reflections, philosophic exploration, and exegetical meditations. It’s written like a spiritual memoir, where he narrates his own story only as a means to glorify God’s providential work of grace.

Structure Puzzle

Finally, glancing at the table of contents, you see that while books 1–9 are generally chronological, books 10–13 cover topics like memory, time and eternity, heaven and earth, and the days of creation. You see that the book’s structure is complex; its topics are wide-ranging. As a rhetorician, Augustine writes his Confessions in the way an artist might arrange a mosaic or a composer might arrange a musical score; each pays careful attention to how every part relates to the whole. He gives extended attention both to key individual episodes in his past life (stealing pears, grieving his friend’s death, ascending to God in a vision), and also to his current temptations (the lust of the flesh, lust of the eyes, and pride of life), precisely to determine how they relate to his whole life and, more broadly, to cosmic history (especially his reflections on Genesis in books 11–13).

The book in front of you is a passionate prayer to God written like a memoir that explores the profound mysteries of God, man, and man’s proper relationship to God.

Why Read Confessions?

Now I want to entice you with seven key themes from Confessions that also serve as seven reasons to read the book.

1. God and Man in Relationship

From the first to the last paragraph, Augustine weaves his answer to three core questions: Who is God? Who is man? And how do God and man relate? He offers layers of answers to those questions, yet all are variations on one major theme from the first paragraph: “You have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you” (1.1.1). God is rest, we are restless, and we find our rest only in God. Discovering how and in what ways that is true is the great task of this book. We all need answers to the fundamental questions he raises; allow Augustine’s deep meditations to guide you.

2. Confessio: Sin, Faith, and Praise

The Latin term confessio — with which Augustine titles his work — tips us off to the expansive nature of the book. Augustine uses the term in at least three overlapping modes: First, he confesses his sin, which is the dominate meaning of the term today. Yet he also confesses his faith, declaring what he believes to be true, like a creed or confession of faith. Finally, from the very first line, Augustine confesses his praise and adoration of God. Augustine’s Confessions expands our sense of confession beyond merely repenting of sin to include declaring our faith and lifting up our praises to God.

3. Rightly Ordered Love and Grief

The scenes from Augustine’s early life reveal that he loved passionately. Intense love meant he was no stranger to grief. At one point, his boyhood friend, whom he loved as the other half of his soul, suddenly died. His heart became “black with grief.” And so the unconverted Augustine commanded his soul to “hope in God” (Psalm 42:5, 11), yet he could not obey “because the dear friend whom my soul had loved and lost was nobler and more real than the imagined deity in whom I was bidding my soul to trust.” Reflecting back, Augustine names his disordered love: “O madness that knows not how to love men as men!” (4.7.12). He loved as if his friend would never die. And he grieved as if God were just imaginary.

Young Augustine’s devastating experience causes him later to reflect on how man can rightly love created things. His answer is that he must “love them in God” (4.12.18). Augustine rejects both Stoic asceticism — as if we could love God isolated from creation — and also Epicurean indulgence — as if we could truly enjoy creation apart from God. Rather, we must love creation as befits creatures; we must embrace our creatureliness in order to properly love created things. And such rightly ordered love will lead to rightly ordered grief. Confessions teaches our restless hearts how to love God supremely, especially in the suffering this life brings, so that we can love the good gifts of creation in and for God.

4. Conversion: The Power of Story

Every person’s conversion to Christ is unique. Yet certain elements feature in every conversion story: bondage to sin, desires for forgiveness and freedom, grace-empowered turning to God. That is why no matter how dramatic or straightforward the sequence of events leading to our surrender before God, we can see similar features in God’s drawing everyone to him. Recognizing this truth, Augustine highlights the power of conversion stories to stir our desires for God in how he narrates his own conversion, which is the climax to books 1–9.

Augustine recounts how three conversion stories contributed to his own conversion. He learned of God overcoming in Victorinus the allure of fame and wealth and deadly pride, and he says, “I was on fire to imitate him” (8.5.10). Stories stoked the desire to follow Christ. Then, like mirrors for viewing his own soul, these stories set Augustine “face to face with myself, forcing me upon my own sight, that I might see my iniquity and loathe it” (8.7.16). It’s remarkable how influential the lives of other Christians were on Augustine. More than knowledge about God, witnessing lives transformed by God drove Augustine toward God.

Given how pivotal conversion stories were to Augustine’s own conversion, is it any wonder he shares his own powerful conversion story? Rereading Confessions at the end of his life, Augustine himself was moved by God’s grace in his past, and he reiterated his prayer that others too — like us! — would be so moved.

5. Strangers to Ourselves (Interiority)

Augustine speaks in many ways as a stranger to himself: he is divided within himself, hidden from himself, and thus a problem to himself. He discovers a stranger in himself both because sin has blinded the eyes of his heart and because, as the bearer of God’s image, he finds a certain mystery in the self that echoes the mystery of the Trinity.

Like a cartographer charting unknown territory, Augustine’s search for rest in God leads him to map his present inner life. Seeking the image of God in his memory, the “innermost part of his soul” (10.25.36), Augustine discovers a still “wounded heart” (10.41.66) desperate for healing. Conscious of this tragic woundedness deep within the self, Augustine calls for Christ, “[his] inmost Physician” (10.3.4), to heal him, the “true Mediator” (10.43.68) to lead him back to God.

6. Redeemed in Time (Temporality)

When Augustine thinks about seeing the whole of his life, he is not merely concerned with who he was and who he is, but with who he will become. And he knows most about who he will become through Scripture’s witness. When he doubts his capacity to make sense of his past and present, he extends, like Paul, toward the future (Philippians 3:12–14). Looking toward his end makes sense of his beginning. Augustine teaches us that God redeems us in time to prepare us for the end of time.

7. Transformational Power of Books

As a young man, Augustine reads Cicero’s Hortensius and “converts” to books. He says, “The book changed my way of feeling. . . . For under its influence my petitions and desires altered” (3.4.7).

But no book looms larger than the Bible in Confessions. While the books of the philosophers awakened a desire for truth, Scripture gave Augustine true knowledge of God. The climax of his conversion comes in response to a child’s voice calling out to tolle lege; “take and read.” Augustine seized Romans 13:13–14, and after reading the passage, “A light of utter confidence shone in my heart, and all the darkness of uncertainty vanished away” (8.12.29). He ends his Confessions with an extended meditation on Genesis 1–2 because he can understand his life only within the Bible’s salvation story, from creation to consummation.

Read Confessions, then, both to see how God transformed Augustine through his Word and to be drawn into the drama of the Word transforming your own life. Tolle lege; take and read.

![]()

Read More

Desiring God