In the nights following George Floyd’s death, the sky along Lake Street in Minneapolis was bright with fire.

Rioters burned an AutoZone, a cellphone store, and the Town Talk Diner. The next night, they destroyed a staffing agency, a Subway, and a Wells Fargo branch. Within 72 hours, they broke glass, stole merchandise, and set fire to hundreds of businesses.

About two miles north—close enough that he could see the smoke—74-year-old John Piper went to bed as normal.

“Slept fine,” he told TGC. Almost nothing fazes him or his wife, Noël, who have been living in a modest house in the under-resourced neighborhood since 1980. They know what to do if they hear gunshots (call 911 and then see if they can help), how to clean up a dozen hypodermic needles from the front porch (use a broom to sweep them up without touching them), and how to scare off someone breaking into your house (open the door and yell at them).

Piper didn’t have a grand vision for city revitalization when he moved in four decades ago. He just wanted to be able to walk to work, and thought it was more authentic to live in the same neighborhood as the church. Soon after, convinced that “presence matters,” he issued a call for Bethlehem members to join him. Within a decade, 400 of them had bought homes in one of the city’s worst areas.

That was 1980, back before cities were cool—long before Tim Keller released Center Church in 2012 or the Southern Baptist Convention aimed the Send Network’s new church plants at urban areas in 2015. But even when moving to the suburbs would’ve made sense—closer to most congregants, more space to grow—Bethlehem stayed downtown.

“The city needs churches,” Piper said. “We shouldn’t abandon neighborhoods for economic reasons. The church had been here for 111 years when I came. God put us here. If we go, this entire side of downtown loses an evangelical church—and there aren’t that many.”

Piper’s people moved in without a master plan, which was both confusing (“What should we do?”) and exactly what When Helping Hurts authors would later advise (start with building relationships, watching, and learning).

Everyone ended up doing something different. But for decades, they’ve kept at it, working through disappointments and challenges, looting and riots, broken glass and homeless tent cities in the parks. They’re still doing it.

John Erickson

As the news about George Floyd was spreading, Target employees began getting texts telling them not to come in. One was the son of pastor John Erickson, who lives across the street from Piper.

“I was like, ‘What’s going on?’” Erickson said. “Then I realized the looting had begun. The city became unhinged Tuesday into Wednesday. There was no police presence and no fire presence Tuesday, Wednesday, or Thursday. I said to our leaders, ‘We have to do something.’”

Erickson has lived in Minneapolis nearly his whole life. His parents moved to the Phillips neighborhood in 1982 after hearing civil-rights activist John Perkins talk about the importance of relocating to broken areas. Though they lived only six blocks apart, Erickson wouldn’t run across Piper until he was at The Master’s University in California and Piper was a “wild-eyed radical” preaching in chapel. Erickson ended up on Bethlehem’s staff for 10 years before planting two churches in the space of three years.

He still leads the second—Jubilee Community Church—which sits less than three miles south of Bethlehem and just one mile from the Cup Foods where Floyd was killed. Since 2009 it’s grown to 175 members who dig into the neighborhood like Erickson does. (For example, when he noticed there were no Little League teams—because the high rate of fatherlessness means no coaches—he started the Phillips Fire Ants.)

During the third night of unrest, “we went to the Target parking lot and set up a prayer tent,” Erickson said. When he asked the police if it was all right, “they said, ‘It’s a war zone. Feel free—it might do some good. But we can’t protect you.’”

So while people broke into Target and stole items his son was meant to be stocking and ringing up, Erickson and his church passed out bottles of water and offered prayer. “We talked to so many people,” he said. “People from our church started to come. One by one, folks came to clean up. But you could feel in the air it was very unstable. We knew—man, this is not going to be a good night.”

It wasn’t. Soon after the Jubilee members packed up and left, someone torched a car a few feet from where they had been standing. Another person was stabbed. The 3rd Precinct police station was overrun and destroyed.

The next night, Erickson sent his wife and younger children to his in-laws while he and his oldest son watched and prayed at home. They got out the garden hose, in case the fires spread to their block. Erickson fielded phone calls from church members with questions like, My block is on fire and the fire department isn’t coming. What should I do? and I think I need to evacuate, but there are too many people outside. I can’t leave.

But even those who did head to family or friends outside of the city were back in a day or two. Over the next few days, many Christians from many churches cleaned up glass, conducted prayer walks, and volunteered with Jericho Road—an organization that provides food and social services to neighbors from Jubilee’s basement.

“We feel like we want to be here over the long-term, making disciples,” Erickson said. “We want to see people really walking with Jesus over the long haul, to see healthy churches established.”

That means being “faithful in the neighborhood, just plodding along,” he said. “On any given day you don’t ever feel like you’re accomplishing that much. It’s just little by little, the Lord helping us.”

Jeff Noyed

The night of the riots, after a full day of ministry, Jeff Noyed was cutting his shrubs.

It wasn’t that he was calloused to what was happening—he could feel the “mounting pressure” in the neighborhood, like “a powder keg ready to go off.” He lives three blocks from Lake Street—he could see the smoke and hear the pops of fireworks and gunfire.

“I really had hoped to be with the other pastors praying in front of the 3rd Precinct during the night,” he said. But Noyed works with under-resourced people, and COVID-19 has been hard on that population. For months already, he’d been working long days, nights and even some weekends, and he was exhausted.

So he pulled his trash cans into the garage so nobody could light a fire in them. And then he did something with his hands so that he could relax his brain.

He trimmed his hedges because they were getting a little long, and because he lives in this community, and because he’s planning to stay.

Noyed has been living in Phillips since 1985 when Bethlehem started a started a koinonia house that would let young people live together while doing outreach to the community.

He met a girl, got married, and bought a house in the neighborhood. Then he bought the place next to him (for a dollar), fixed it up, and rented it out. Then he befriended his neighbors on the other side—evacuees from Hurricane Katrina—even taking their boys on a trip to the Boundary Waters. He watched them come to Christ, and for that alone would do it all again.

Noyed has been doing inner-city ministry for 28 years. He leads Jericho Road, the ministry that operates out of Jubilee’s space. He and two assistants (and about 30 volunteers) connect people to social services, help with resumés and state identification, assist with crisis finances, and pass out food. Even before the riots, COVID-19 made 2020 an extraordinarily challenging year.

“In March we distributed 50,000 pounds of food,” Noyed said. “In April, we did 108,000. In May, we did 128,000.”

When the riots took out the neighborhood’s grocery stores, Jericho Road set up pop-up food shelves on Lake Street. Now Noyed and his volunteers are working on the next problem—passing out water and hygiene items to the hundreds of tents the homeless have set up in neighborhood parks after the city declared them places of refuge in June.

“Some [tent occupants] come from out of town to protest and have stayed,” Noyed said. “Some come from the Native American reservations, seeing this as an opportunity to get a job and relocate.” He’d like to be involved in finding housing resources for them. One option might be the apartment complex bought and operated by former Bethlehem—now house church—members Jim Bloom and Cecil Smith. (“They serve the highest-poverty people in the neighborhood, and they manage it in accordance with kingdom values,” their friend Russ Gregg said. “They’ve ministered to hundreds of people over the years.”)

Noyed remembers his father’s incredulity when he told him, decades ago, that he was moving into Phillips. His dad wasn’t against helping, but thought Noyed could still do that while living in a safer place.

And that’s true, Noyed admits. He could’ve done that. Lots of people do.

“But living in the neighborhood gives you a distinct understanding,” he said. “You have the opportunity to be involved with block clubs, with Bible groups, to be there for gunshots and murders and stolen cars.”

And police injustice and rioting and homeless tent cities. And people coming to Christ and having enough food to feed their families and getting on their feet financially.

“There are hard days, believe me,” he said. “But overall, the word I’d use to describe ministry here is a privilege.”

Russ Gregg

The night of the riots, Russ Gregg wept.

“It was probably the saddest day of my life,” he said. “We’ve lived here for 30 years, and to see the progress being destroyed in a moment was heart-wrenching.”

And it’s true—Phillips had been slowly improving. After the white flight of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, the presence of Bethlehem members and others helped stabilize the neighborhood. At the same time, cheap housing drew refugees—especially those fleeing war in East Africa in the ’80s and ’90s, City Vision executive director John Mayer said. “Basically, the immigrants rebuilt it, and the Christians started to pray and evangelize and care for the people,” he said.

Today more than 100 languages are spoken in Phillips—most often Spanish and Somali. Ethnic shops sprang up, and in 2006 an enormous abandoned Sears Building was revitalized. It’s now home to Alina Health corporate headquarters, the Midtown Global Market, and residential lofts. It’s also where much of the rioting happened, with dozens of businesses in the global market destroyed.

“On the very night our city was being destroyed in the riots, we had our annual dinner for the high school seniors,” Gregg said. His school was born 20 years ago after he listened to Piper preach about venturing something for God that’s “a little bit crazy.” The next day, Gregg quit his job as development director for a Christian school in one of Minneapolis’s wealthiest suburbs and launched a classical Christian school in Phillips.

Twenty years later, Hope Academy has grown from 35 students in a church basement to 500 students in a seven-story school building. In an area where graduation rates for children of color are some of the worst in the nation, students at Hope Academy learn Shakespeare, practice virtues, and earn college scholarships.

“The formation of servant leaders who have the academic qualifications—but more than that, the heart qualifications—to be the servant leaders of our city is crucial,” Gregg said.

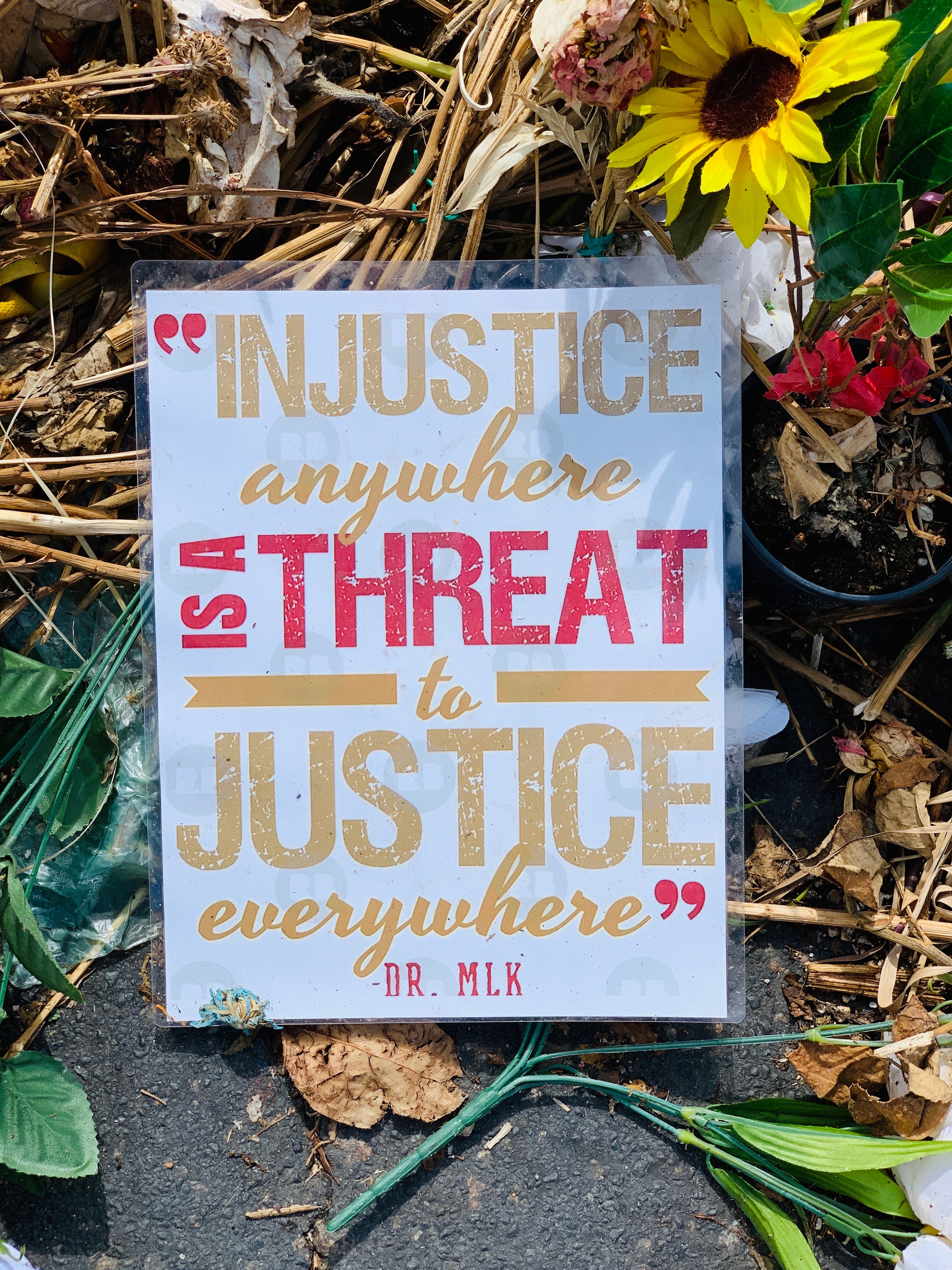

While their neighborhood broke and burned, Hope’s class of 2020 met on Zoom to celebrate their graduation and hear individual tributes from their teachers. At the end of each, the teacher told them, “Hope Academy has covenanted with your family to prepare you as a kingdom citizen. Now is your time to work for justice and economic opportunity and racial harmony and joy in the community. Remember that Jesus came not to be served, but to serve.”

“We heard that refrain 21 times,” Gregg said. “As we were praying, we were all thinking, Our city needs these future leaders now more than ever before. It was one of the most poignant moments. I’ll never, ever forget that.”

The global pandemic, economic uncertainty, racial injustice, and riots of the last five months can make it feel like God has abandoned Phillips.

“But he hasn’t,” Gregg said. “And he may even be orchestrating this to bring about his kingdom purposes.” Gregg can glimpse this already—his teachers have had more contact with student families than ever before, calling regularly to check in. They delivered groceries to some, paid to replace another’s broken refrigerator, provided quarters so another could use the laundromat (because the bank, where you normally get quarters, was in shambles). Hope set up a COVID relief fund to help families with tuition and received almost $100,000.

Next Gregg worked on calling city council members about the tent cities. The dirty syringes, sexual assaults, and violence in the encampments meant the children of Phillips couldn’t play in their parks. Since July, most have been dismantled.

“At the end of my block, there were 30 tents in an empty lot. At the park adjacent to Hope Academy, there were another 10 to 12 tents,” Gregg said. “An 18-year-old was shot in that park the other week. It feels like living in a war zone.”

But Gregg stays, because he knows it’s a war that can only end one way.

“God is going to win,” he said. “The kingdom is going to triumph. That’s ground for hopeful risk-taking, for acts of love. . . . It’ll be interesting to see, in the next four to five months, how God uses his people he’s got planted here to love and to serve and to lead in important ways.”

Ming-Jinn Tong

Ming-Jinn Tong wasn’t in the Phillips neighborhood the nights it burned. Though he had lived there for a decade, he’s since moved to another neighborhood north of the city.

But Tong, who is the pastor for neighborhood outreach at Bethlehem, showed up first thing the next morning.

A friend had called, asking if he wanted to join her family in picking up glass. “I made a Facebook event, and mainly just shared it on my own page for people in the neighborhood,” he said. “Within an hour, I had 1,200 shares of my event. It was crazy.”

When he met his friend an hour later, another 400 people pulled up.

“It was just people from all over the Twin Cities [of Minneapolis and St. Paul],” he said. “I don’t know who they were. So we did a bunch of cleanup. Because I’d done literally 10 years of neighborhood cleanup, I knew what to do.” (Call the hardware-store owner who stores the gloves and bags for cleanup efforts. Ask the city for yellow garbage bags, which signify the garbage has been gathered by volunteers, and which the garbage trucks will pick up for free. Stack the filled bags along the curbs.)

The next morning, the rioting damage was even worse, and spread farther out from Lake Street. Tong and his friend Nick Stromwall went to the church and pulled together a Support the Cities web page.

“We basically said, ‘We’re making this page to help people know where the damage is, where the needs are, and where you can go to get help,’” Tong said. “Within five days, we had almost 22,000 followers. I think we mobilized about 8,000 people—judging from Facebook stats—to come to 30 events we created.” (They also promoted others’ events.)

Support the Cities took off because it’s filling a need at just the right time. But the reason Tong was able to act so nimbly was that for years he’d been waving to neighbors, listening to stories, and finding out who could help with what. (He was so present that when his backyard neighbor shot his wife and daughter, he asked Tong to adopt his son when he went to prison.)

That past faithfulness is the reason people trust him to stick around now. Over the years, Bethlehem has run an ESL ministry for immigrants, facilitated weekly grocery pickup and Bible studies for subsidized housing high-rises, and worked with local neighborhood associations to clean up garbage, address security concerns, and hold festivals.

“Our methodology, at least under my leadership, has been participation and service and sharing the good news through established relationships,” Ming said. He knows it hasn’t been done perfectly, but “we cannot—for the sake of not doing it right—do nothing.”

Tong’s main goal now is to “make connections with other organizations in our neighborhood,” he said. That’s an important point—Bethlehem isn’t the only group working in Phillips. They’ve often partnered with other churches or organizations over the years. Tong attends council meetings, goes to gatherings of neighborhood leaders, and talks with officials for land use or housing development.

“All of life is outreach,” Tong said. He encourages church members living in Phillips to include unbelievers in their everyday lives, to participate in what they’re doing, and along the way, to be a gospel light. “Our whole life is a living sacrifice.”

John Piper

A smoking Lake Street isn’t enough to push Piper out of the neighborhood.

His car has been broken into, his sons’ bikes stolen out from under them. A few weeks ago a boy asked if he could cut the grass. Piper said yes—he always does when a kid wants to work. But later the boy came back with a friend and tried to jimmy the window open. “Noël and I were sitting five feet away, watching them do it,” he said. “I opened the door, and they bolted.”

Days later, Piper heard a crash and saw a car rolling onto the sidewalk. One driver got out and shot the other, wounding him. “There was a lot of blood for an arm,” noted Piper, who called 911.

“One of my biggest battles over the years is not to become jaundiced,” Piper said. He feels the failures more than the successes. “One of my greatest regrets is how little impact we seem to have had in the Native American community.” Nor is Bethlehem as multiethnic as he hoped it would be. Crime is still common—even more so in this most recent season.

But then, there are moments like this:

“I was sitting in the backyard at the picnic table having lunch a few weeks ago,” Piper said, “and a guy in his 20s stops and says, ‘Hey—I haven’t seen you in a long time. You’re still here. I used to shoot buckets in your driveway as a kid. People used to tell me I lived in a bad neighborhood. And I’d tell them—no way. A pastor lives down on the corner.’”

Piper concludes: it’s pretty hard to quantify the kinds of influence that happen by long-term presence.

Piper concludes: it’s pretty hard to quantify the kinds of influence that happen by long-term presence.

At the same time, it is important to have gospel-centered expectations.

“When I read 1 Peter,” Piper said, “his expectations for the people being won to Christ do not appear to include cultural transformation. The expectation is: Keep on declaring the excellencies of the One who called you, and keep on doing good deeds. Some people will be moved to faith and others will go on maligning.”

Peter doesn’t talk like an urban renewal specialist, Piper said. He uses phrases like “you have been grieved by various trials” (1 Pet. 1:6) “when they speak against you as evildoers” (1 Pet. 2:12), “endures sorrows while suffering unjustly” (1 Pet. 2:19), and “do not be surprised at the fiery trial” (1 Pet. 4:12).

In other words, the Bible doesn’t promise that if you move into a neighborhood like Phillips, people will trade drugs and violence for hymn sings and stable family structures.

“But they might see your deeds and give glory to God,” Piper said. “Your job is to be there, love people, declare the truth, and give a reason for the hope in you. My job is faithfulness. God’s is fruitfulness. We want fruit. But staying in the city does not depend on it.”

He’s a lot less worried about being taken advantage of than he used to be. “I used to pride myself that I could see through lies and get people to contradict themselves when they were asking for money,” he said. “But gradually the Lord made it clear to me that at the judgment day there will be no rewards for shrewdness, but only for love. And Jesus’s commands to turn the other cheek, and to give your cloak as well as your shirt, and to go two miles not just one—all of that showed me that being taken advantage of is normal.

“Jesus cares as much about killing my selfishness as he does about who gets what money. The issue for me is: will I be content in him so that being taken advantage of is no big deal?”

At the judgment day there will be no rewards for shrewdness, but only for love.

After 40 years in the neighborhood, Piper would do it all again. “I really believe that preaching the whole counsel of God decade after decade in a way that grows a life-giving church—mingled with regular calls to do crazy things for Jesus, undergirded with big-God theology, and an example of urban presence—makes a big difference.”

And so he keeps hiring kids to mow the lawn, and handing out New Testaments on his jogs through the neighborhood, and talking to the homeless. During the weeks after Floyd’s murder, Noël went every day to volunteer for the food shelf at the predominantly African American Greater Friendship Missionary Baptist Church. And other Christians in the neighborhood lead block clubs, plant community gardens, pick up trash, volunteer at the park district, and pray with neighbors.

“When somebody says to me, ‘If you could choose any place in the world to live, where would it be?’ I’d say, ‘Where Noël is,’” Piper said. “And then, ‘Where the needs are.’”

Read More

The Gospel Coalition