If you ask most New Testament scholars for the most influential book in their field, John Barclay’s Paul and the Gift will regularly top the list.

The book was published in 2015 and is a tome, with more than 600 pages of dense argumentation and writing. For those trying to keep up with current trends in research, the book was literally a weighty gift.

Now readers can be thankful because Barclay has condensed, summarized, and even supplemented his argument in less than 200 pages. Though the argumentation is still precise, Paul and the Power of Grace is a welcome and more accessible edition. Barclay—professor of divinity at Durham University, England—summarizes the key points of his earlier work, takes the exegesis beyond Romans and Galatians, places his work in conversation with other Pauline interpreters, and gives practical application.

Argument: Unconditioned but Not Unconditional

Barclay’s two books concern what we mean by the word “grace” (charis), which can also be translated as “benefit, favor, or gift.” He notes there are different ways of understanding it. Theologians have been less than precise when they speak of “free grace” or “pure grace.” In what sense is it free?

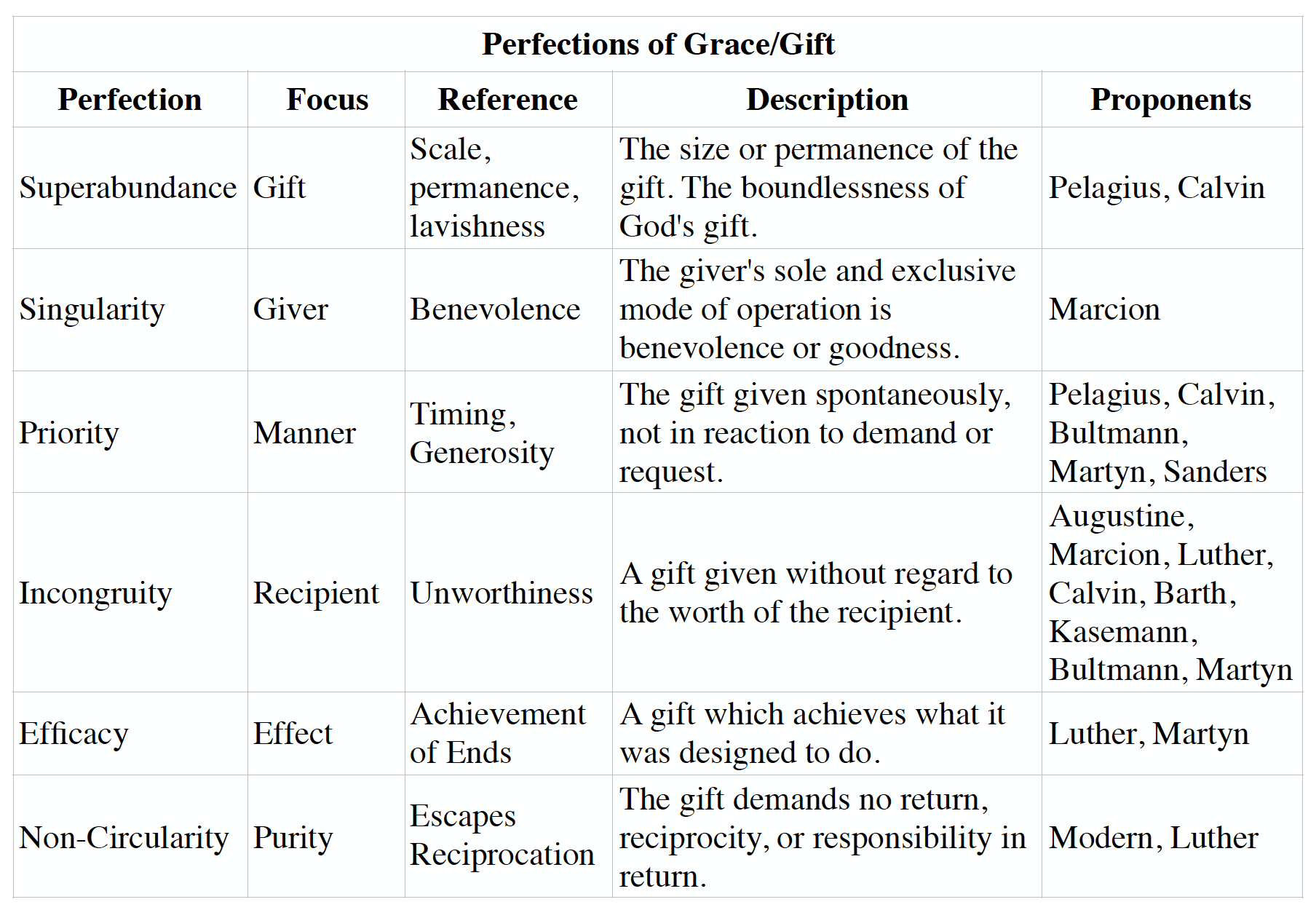

Some might say it’s in the scale of the gift (superabundance), others might attribute it to the goodness of the giver (singularity), or the timing of the gift (priority), or that the gift is given without regard the worth of the recipient (incongruity), or a gift that achieves what it is supposed to do (efficacy), or that the gift demands no return (non-circularity). This last category is the most modern and maybe the most pervasive in American evangelicalism. However, the idea is found almost nowhere in the ancient world.

Different interpreters through history have concluded one of these is the ultimate perfection of grace in the Bible. More recently, this question concerning the nature of grace has gained fresh relevance ever since E. P. Sanders, father of the New Perspective on Paul, argued that Judaism is a religion of grace.

But what did Sanders mean by “grace”? Is it what the biblical authors meant? Most say Sanders implied that Judaism was a religion of grace in terms of priority: Israel was saved first and then given the law, not given the law in order to be saved.

Essentially, Barclay argues that Paul “perfects” grace in terms of incongruity: God’s grace is so amazing because the gift of Jesus Christ is offered to all, without regard to worth. But Barclay also pushes against the notion that this means nothing is to be given back in return. Gifts in the ancient world always required reciprocity. Therefore, the gift of Jesus Christ is unconditioned, but not unconditional. It demands a response.

New Additions

Barclay expands his gaze to more Pauline epistles than Romans and Galatians. He contends that the unconditioned but conditional nature of grace is the grammar of Paul’s theology. Much of Paul’s antithesis demonstrates that Paul’s theology is one of incongruity: the unrighteous are made righteous, rebels are made sons, the weak are made strong, the foolishness of God is wiser than the wisdom of man.

Barclay also contends that grace isn’t so much a thing as a person in Paul’s theology, and that his theology has a circular shape. In other words, God’s grace is given, which leaves us with gifts, which we use to enrich others (1 Cor. 1:4–7; 12:4–11; 28–30).

In the final two chapters, Barclay places his work in conversation with other “Pauline Perspectives” and applies the work to today. The other Pauline perspectives include the Traditional Perspective on Paul, the Catholic Perspective, the New Perspective, and Paul within Judaism.

Barclay says his work finds commonalities with all the schools of thoughts, but also challenges them. The traditional perspective needs to realize “free grace” doesn’t mean lack of benevolent response. Grace is unconditioned but not unconditional. (Have I said that enough yet?) Barclay also challenges the common tendency to place faith and works in antithesis. In response to the Catholic perspective, Barclay finds no evidence for two stages of grace (initial grace in justification and final grace in the eschaton). Nor does he believe that Paul sees grace as a thing to be transferred to believers (“habitual grace”). The New Perspective, while right on many accounts, has located the problem in ethnocentrism, whereas Paul’s gospel was founded not on a more inclusive gospel but “the incongruous grace of God in Christ, given without regard to ethnic (or any other) worth” (144). The “Paul within Judaism” school rightly recognizes Paul as a Jew, but his response is more subtle than a simple rejection or acceptance of Judaism. The gift of Jesus Christ recalibrates everything, including Jewish allegiances (147).

In the final chapter, Barclay shifts to practical implications and application. Social practice is a necessary result of Christ’s gift. While grace is free, it also makes demands. This means the grace of Jesus Christ challenges communities to confront boundaries and established hierarchies of worth. He relates this to questions of class, race, and the disabled: “Paul’s theology of grace is, in fact, a rich resource for Christians in challenging racism, gender prejudice, and all forms of negative stereotype” (152).

Response

Overall, we should be thankful for Barclay’s analysis. Some of the best works provide more clarity and depth to current conversations and present categories for understanding matters more precisely. When I teach in the classroom, I give a brief summary of Barclay’s work and students regularly find it helpful. They’re also thankful they didn’t need to read 600-plus pages after my summary.

Barclay’s work attempts to chart somewhat of a mediating territory on the “perspectives” on Paul, which I find refreshing. He recognizes helpful slants stemming from various schools, yet he’s also willing to critique them. I was surprised he didn’t engage more with the apocalyptic perspective on Paul, especially with his emphasis on incongruity and antithesis.

As someone who has been influenced most by the Traditional School on Paul, I think Barclay’s clarification on grace not being unconditional is a needed word. It’s also true, though, that the best of the traditional school has recognized this in other realms. Divine agency precedes but is paired with human agency. Bonhoeffer worked hard against cheap grace. Barclay is right to argue this paradigm should be applied to the “grace” concept as well.

I also wonder if incongruity could regularly be combined with priority. For example, in 1 Corinthians 1:4 Paul thanks God for his grace to the Christians in Corinth. This leads to no lack in spiritual gifts, which hints at the priority of God’s gift for their gifts. It would be interesting to explore how multiple “perfections” could be at play in certain passages, while also recognizing one might take precedence.

It seems that Barclay leans slightly toward the New Perspectives on Paul school. I say this because his critique of the new perspective is close to a distinction without a difference. He critiques the New Perspectives for centering on ethnocentrism and says it should include any other “worth” (144). New Perspectives proponents would likely agree. Paul takes any form of human worth and substitutes the cross. But they would also affirm the ethnocentrism is primary in Paul’s context of planting churches with Jews and Gentiles.

His critique of the Traditional Perspective on Paul partially landed and partially didn’t. There already is a strong tradition in some traditional-perspective camps that affirms a type of unconditioned-but-conditional salvation. I think many would heartily agree with Barclay when he says:

Nor does Paul play off divine against human agency, as if the effect of grace is to replace the human actor with the action of the Spirit. To be sure, the believer’s agency is now energized by, and enveloped within, the agency of the Spirit/Christ, but it would be misleading to deploy here a generalized contrast between passive and active, grace and work (140).

Though a more radical unconditional view may have been true in the past, more works today affirm a form of conditionality to salvation, as well as the interrelationship of human and divine agency.

Barclay’s second critique of the Traditional Perspective concerns narrowing the discussion to faith versus works (another hint toward his more New Perspectives view). Emphasizing the incongruity of grace, however, points toward a more wide-ranging view of worth that includes ethnicity, ancestry, social status, and gender. Thus, Paul doesn’t pit faith versus works, but any sort of “worth” versus faith. In other words, both the New Perspectives and Traditional Perspective narrow the conversation too much. The New Perspectives focus on ethnocentrism, while the traditional perspective focuses on a self-reliant or self-made salvation.

However, I still tend to think Paul can use “works/works of the law” (Rom. 2:6; 4:4; 11:6; Eph. 2:9; 1 Tim. 2:10; 5:25) as an overarching category for worth, expressed in one of its most pervasive forms that’s also tied to ethnocentrism. The danger for Barclay, I believer, is missing some of Paul’s main emphases that both the New Perspective and Traditional Perspective helpfully point out. In fact, one might even question whether his critique is simply a generalization of the two schools and therefore not a critique at all.

Having said that, Barclay is asking both camps to expand their horizons, and that advice is usually good. Interpreters do have a tendency to narrow their focus and see what they’ve always seen. Barclay is simply affirming that his work on “grace” has stretched his own viewpoint.

Think More Precisely

I think every pastor should read Paul and the Power of Grace. The concepts Barclay presents will be in conversation for a long time, and commentaries will begin to engage with his work.

Readers may not agree with all of Barclay’s conclusions, but the book will make them think more precisely about grace. And that is never a bad thing.

Read More

The Gospel Coalition