Though I spent a good deal of my childhood in the red-backed pews of a Southern Baptist church in rural Illinois, I can recall only a handful of memorable sermons. None sticks in my mind more than one from a traveling evangelist who kept referring to Bible-believing Christians in the United States as a “remnant.”

The prophet Isaiah frequently used the word to describe a small group of Israelites who would survive foreign invasion and oppression, but would eventually return to the land of Israel and fulfill the promise God gave to Abraham (Isa. 10:20–22; 11:11–16; 37:1–38).

That preacher drew a line between the remnant of Jews who survived the Assyrian army, and American evangelicals who are constantly pressed by the forces of culture to change their beliefs and become more mainstream. Tales of oppression in the 21st century were woven in and through the oracles of Isaiah as the evangelist pounded the pulpit.

Is that a good comparison? Are evangelicals an American remnant?

American Remnant

As I grew up in that evangelical church, the narrative of oppression was always in the background. When I began my doctoral studies in American religion and politics, I quickly understood just how central these stories are to the evangelical experience. One preeminent scholar of religion, Christian Smith, summarized this worldview in his 1998 book, American Evangelicalism: Embattled and Thriving.

After looking at the data for the last 10 years as a quantitative social scientist, I can say with certainty that although there are clear reasons for concern, evangelical presence in the United States is stronger than ever before.

The persecution narratives always centered on a tentpole––evangelicals were a shrinking remnant of people who were faithful to the gospel, while many Americans were secularizing, and other Christian traditions were liberalizing. And in some senses, this narrative isn’t wrong. We have seen our broader society move away from Christian norms such as a biblical definition of marriage, two fixed sexes determined by God, and public prayer.

But after looking at the data for the last 10 years as a quantitative social scientist, I can say with certainty that although there are clear reasons for concern, evangelical presence in the United States is stronger than ever before.

Born Again

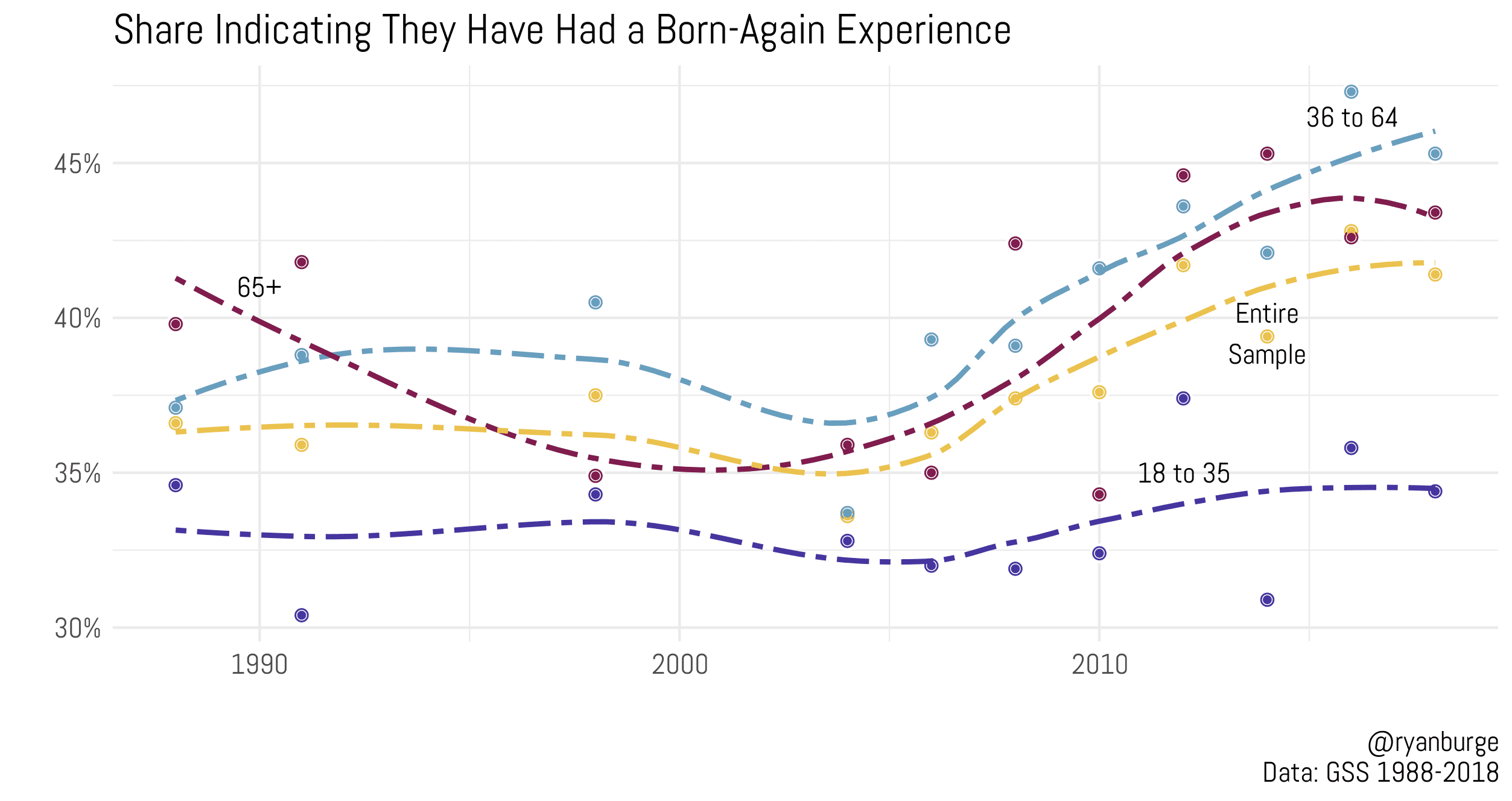

The General Social Survey began asking this question in 1984: “Would you say you have been ‘born again’ or have had a ‘born again’ experience––that is, a turning point in your life when you committed yourself to Christ?” No matter how the sample is divided based on age, the conclusion is clear: those who have had a born-again experience are more plentiful today than at any other point since the mid-1980s.

Just about 36 percent of Americans said they were born again in 1998. Thirty years later that number had risen to 42 percent, and all the increase occurred between 2006 and 2018. The percent of born-again seniors rose from about 35 percent in 2000 to 43 percent in 2018. Nearly half of those between 36 and 64 now indicate a born-again moment in their lives. Among the youngest American adults, the share who are born-again is not statistically different today than it was three decades ago.

Just about 36 percent of Americans said they were born again in 1998. Thirty years later that number had risen to 42 percent, and all the increase occurred between 2006 and 2018. The percent of born-again seniors rose from about 35 percent in 2000 to 43 percent in 2018. Nearly half of those between 36 and 64 now indicate a born-again moment in their lives. Among the youngest American adults, the share who are born-again is not statistically different today than it was three decades ago.

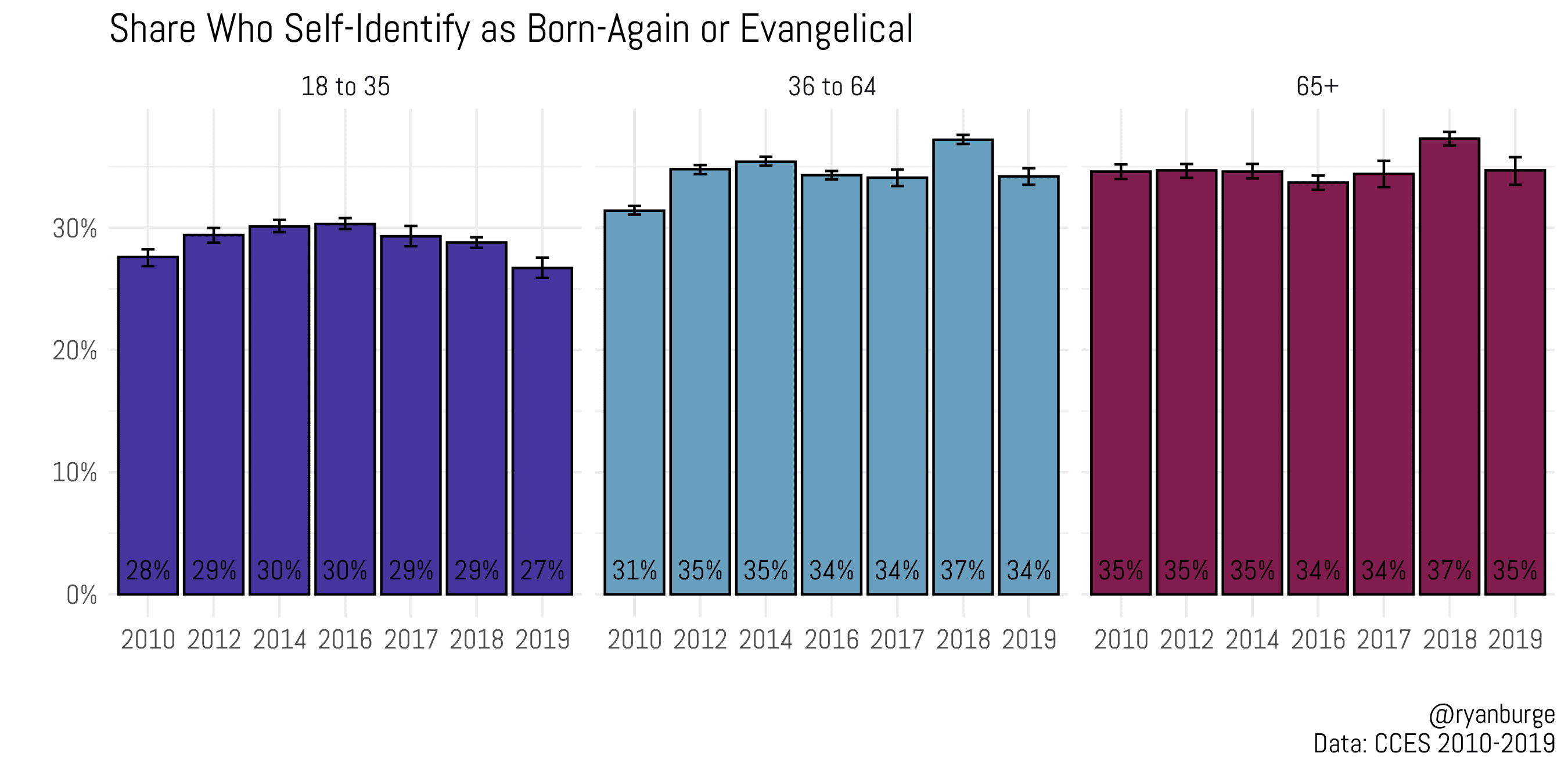

But while the General Social Survey asked if respondents ever had a born-again experience, it didn’t ask if people still identify as born-again or evangelical. Fortunately, the Cooperative Congressional Election Study did ask. While the time frame is not as long as the survey, the same pattern persists here.

In 2010, 28 percent of people between the ages of 18 and 35 identified as evangelical. In 2019, that number had barely moved (27 percent). The share of those between the ages of 36 and 64 who identify as evangelical rose––from 31 percent to 34 percent––during the same time. For the oldest age group, the share who currently identify as evangelical has not changed.

In 2010, 28 percent of people between the ages of 18 and 35 identified as evangelical. In 2019, that number had barely moved (27 percent). The share of those between the ages of 36 and 64 who identify as evangelical rose––from 31 percent to 34 percent––during the same time. For the oldest age group, the share who currently identify as evangelical has not changed.

There’s no evidence here of any real decline––and maybe even some modest growth among those in the middle-aged group.

But that doesn’t mean all is well.

Faithful Living

When the veneer is peeled away, some troubling factors emerge. While evangelicalism is holding steady as a share of American Christianity, evangelicals are less involved in worship than they were just a decade ago. What’s truly surprising is that older evangelicals are less likely to attend church faithfully.

What’s truly surprising is that older evangelicals are less likely [than younger ones] to attend church faithfully.

In 2010, a little less than 19 percent of retired evangelicals said that they “never” or “seldom” attended church services. By 2019, that share jumped to over 24 percent of those 65 and older. At the same time, the portion that attended weekly or more dropped by four percentage points.

That same general pattern also emerges for those between 36 and 64 years old––rare attendance is up about five percentage points, and weekly attendance dropped about the same amount.

But here’s a ray of hope: church attendance is up among younger evangelicals during the same time. The share attending “seldom” or “never” dropped about three percentage points, while “weekly” or “more than weekly” attendance jumped nearly four percentage points. In 2019, evangelicals younger than 35 were more likely to attend weekly than those in the middle-age group were.

How do we make sense of the fact that older evangelicals attend church less, while younger evangelicals attend more frequently?

How do we make sense of the fact that older evangelicals attend church less, while younger evangelicals attend more frequently?

One possible explanation is that evangelicalism is becoming more culturally distinct among younger Americans. The share of millennials and Generation Z who have no religious affiliation is more than 40 percent now––nearly double the rate of Baby Boomers. Christians in their 20s who welcome the “evangelical” label place themselves in clear opposition to prevailing trends among their friends. It makes sense that only young people who feel spiritually connected to theological evangelicalism are willing to embrace it.

It makes sense that only young people who feel spiritually connected to theological evangelicalism are willing to embrace it.

If numbers are the only concern, American evangelicals have no cause for alarm. They will still have a huge effect on the culture and politics of the United States for years to come. But being a remnant, in my estimation, also means fidelity to the theological roots of the evangelical tradition, not just checking a box on a survey.

Some Americans seem to have embraced a conception of evangelicalism that is less about the gospel and more about cultural and political power. If this trend continues, those who wish to remain faithful to the historical definition of evangelicalism will have a harder time convincing the larger culture that their true motivations are theological—and not just about maintaining power in the public square.

Theologically orthodox and active evangelicals may be the true remnant inside the larger movement.

Read More

The Gospel Coalition