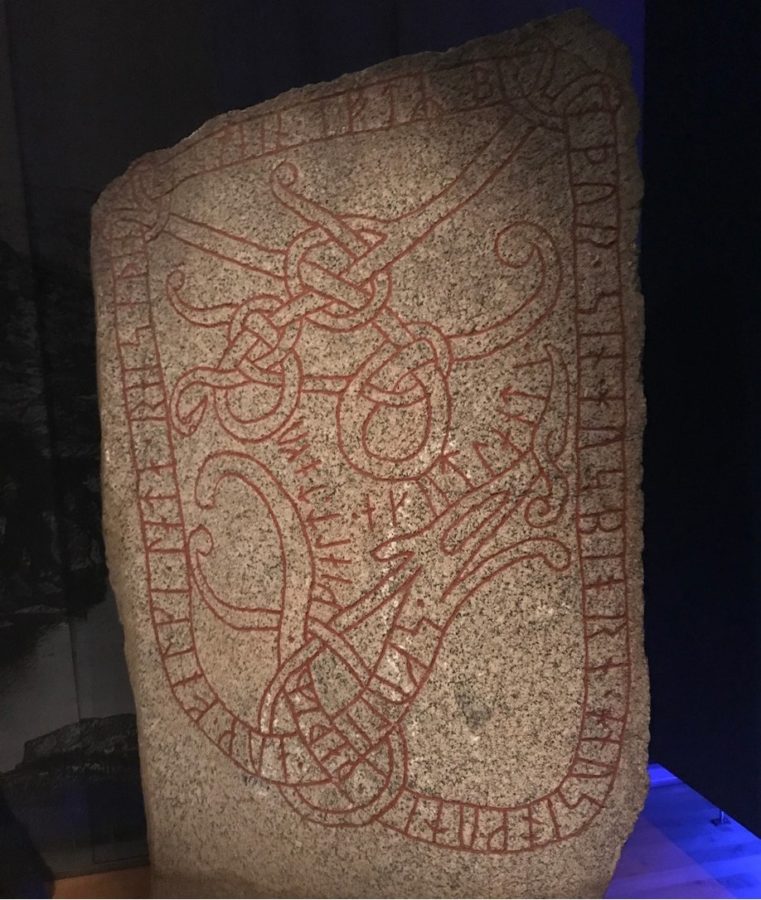

When visiting an exhibition about the Viking Age at the Museum of History in Stockholm I came across a memorial runestone that had been raised by Skuli and Folki in Torsätra in Uppland,[1] telling about their brother Husbjörn, who had died of sickness while collecting taxes in far away Gotland. Now, some years later, I found my photos of the stone, and it got me thinking that the stone might have something to tell us about the nature of taxes. The short runic inscription also tickled my imagination, and I started to wonder if maybe what happened was something like the following:

Gotland, Sweden, year 1061 AD

Side by side, Gunnar and his robber chieftain, Husbjörn, move swiftly and quickly. They decide that the battle is at the point where they can, and should, take on Uffir, the owner of the farm. With his strength and readiness he is injecting courage into the defense. Initially, Gunnar and Husbjörn are successful in their move.

Uffir’s roar of pain is heard loudly over the alarm of the tumultuous raid when Husbjörn, using his shield, knocks Uffir’s sword arm out of joint.

Furious with the bandits’ attack, and full of fear for his life and those of his loved ones, Uffir is pumped to the brim with intoxicating adrenaline. This makes him hold his ground despite the numbing pain and able to parry Husbjörn’s blow toward his neck. But this is not the first time Husbjörn and Gunnar have performed this maneuver: the chief launches a heavy attack using his shield, then his sword, after which Gunnar follows up.

Thus, Husbjörn is not surprised when his face is flooded with a warm and sticky stream of blood. He grunts with excitement when he feels the irony taste.

Only, it is not Uffir’s blood.

Gunnar’s throat is slit wide open by the firm pull of a short and very sharp blade. It is the steady hand of Ylva, Uffir’s wife, holding the sword. Where she came from is not a question presenting itself to Husbjörn, as he has been momentarily blinded by the stream of blood splashing his face. At the moment he is oblivious to the fact that Gunnar has been slain as well as about who his undoer is.

Likewise, it is only later that he learns who stabs a sword, still dripping with Gunnar’s blood, deep into his mouth. Husbjörn backs away from the blade, painfully pulled out of his face. He manages to raise his gaze enough to realize that he can now choose between flight and death. His eyes, briefly meeting Uffir’s, do not find the slightest trace of mercy in the defender’s raging face. The arm that Husbjörn and Gunnar have left unharmed is massive and strong, and fully prepared to repay the debt that the robbers justly deserve.

It turns out that Husbjörn shall not die by Uffir’s hand. He is saved by his band of bandits, which loses two more lives to the farm’s defenders before they retreat, head over heels, without any of the wealth they came to plunder.

Back at their camp, the efforts to save Husbjörn’s life begin, but he can neither eat nor drink. His deep wound gets infected and reeks so badly that his men draw straws for who will pour water into the mouth of their chief.

Husbjörn dies a few days later, slain by a woman who refused to let herself or her family fall victims to robbers and bandits.

The day after his death, Husbjörn’s brothers, Skuli and Folki, arrive, rich and almost unharmed from their more successful raids and pillages elsewhere. They arrange for a Viking chieftain’s funeral for him.

Once back home in Torsätra in Uppland, Skuli and Folki consider what should be Husbjörn’s legacy. Yes, their brother died in battle, but it was by the hand of a woman, and he chose to flee. They decide that his stone will tell that he died from sickness. They also tell the runemaster to inscribe that it was while collecting debt:

Skúli and Folki have raised this stone in memory of their brother Húsbjǫrn. He was sick abroad when they took gjald on Gotland.

Torsätra runestone (ca. 1060–70); photo by Peter Strömberg

“Gjald” as a Euphemism for Theft

Gjald was the Old Norse word for debt and is what robber Vikings called the kind of theft that Husbjörn was engaged in. The word made the victims seem like they owed the perpetrators something. If they did not voluntarily pay their “debts” the violence brought upon them was justly deserved.

The heirs of the robber Vikings inherited this trick but instead used the word “taxation.” They also made it so systematic that today it is uncommon to hear of anyone resisting taxation firmly enough to warrant the actual use of the violence always backing the threats.

It might seem silly to call theft by another name, obfuscating what it really is. Who buys that Husbjörn from Uppland would have any gjald to collect on Gotland? Who in their right mind would even briefly consider that Uffir and Ylva, their children, and the people living with them at the farm and working for them, could have deserved the violence brought upon them by these uncivilized brutes? However, it is of utmost importance for the robbers to use words that hide what is really going on. This helps when recruiting people to join the raids: being humans, we want to consider ourselves the good guys. It also weakens the victims in their efforts to summon kinsmen to their defense. The importance of how the story is told cannot be underestimated. This was all too well understood by Gustav Eriksson Vasa, in Swedish schools often referred to as the founding father of Sweden.[2]

Gustav Vasa had made large portions of what we today call Sweden succumb to his power, but there were pockets of rebellion. The fiercest of the rebels was Nils Dacke, who managed to summon large armies to resist Vasa’s raiding and his Protestant policies.[3]

For a long while the king’s armies did not suffice to overcome Dacke.

The crown’s remedy was highly efficient slander campaigns in which Dacke was portrayed as the lowest of cowards. Dacke’s armies shrunk as his reputation was tarnished, while the king’s war recruitment was facilitated. Unlike our fictional heroes, Uffir and Ylva, Nils Dacke paid the ultimate price for his resistance to the king’s abuse. He himself died in battle, but Gustav Vasa then murdered his entire family.

Of course, it takes time to craft a lie out of a foundational truth—from rightfully defending oneself and one’s property to dutifully, sometimes even proudly, giving up what belongs to you.

It is not a small task that the robbers need to carry out—to change a state of affairs in which most people know that they have the right to defend themselves when someone stronger comes to take their belongings, where everybody does not immediately agree that renaming theft is a spell strong enough to dematerialize the crime. The robbers cannot tolerate or afford the risk that victims may prove both willing and able to defend themselves. Husbjörn and his band of robbers would agree.

However, time to ride out temporary slumps is something the robbers have in abundance, as long as they retain their capacity for violence. It’s noteworthy that as far as the victims are concerned, the development from dictatorship to democracy has not brought a single day of respite from systematic theft. Once it was the armies of self-proclaimed kings who committed the raids. Today, the subjects are allowed the tiniest sliver of imaginary say over who should wield the keys to the machine that keeps the thievery going.

The robbers use their time to erode the natural insight into what their plunder is. The collection of taxes would have been much more expensive and difficult if things had remained as they were during the Viking Age, or even in the days of Nils Dacke—with people who stand ready to defend themselves and what is theirs. This is why the powers that be stride in the footsteps of Gustav Vasa, cultivating the myth that ”the state is us”—that we, ourselves, have in fact decided that we should be looted of that which is ours.

Today the state has taken things so far that it has gotten its subjects to completely forget that taxation is theft. With this the desire to keep one’s own property, and to be the sole master over how it should be used, has transformed into egoism of the lowest variety. Something as obviously true as that taxation is theft is regarded as an opinion, and, even if fringe, a very unpopular opinion at that.

One Thousand Years Later, Taxation Is Still Theft

But in substance, nothing has changed. Taxation is theft. It is theft because it is not voluntary to pay. When collecting taxes, the state still stands ready to use massive violence in order to force its subjects to pay. As it is also ready to use violence to force some subjects, such as employers and shopkeepers, to assist with its stealing from other subjects[4]—something that most people would refuse to do if the proper terms were used in place of taxation.

The state reaps colossal rewards from the patient use of its time, moving the goalposts deliberately and gradually. Most of its subjects are now conditioned to respond to the message that taxation is theft with ridiculously predictable objections. They say things like:

● ”But we get free education and healthcare!” (Which ”free” goods are enumerated depends on the particular state.)

● ”Who would build the roads?”

● ”You can always leave.”[5]

The last of these objections is partly a fallacy in reasoning: ergo decedo.[6] It is mostly used as a way to try to stop someone from informing others that taxation is theft. Imagine if all objections against how things are were met with the ”argument” that you should leave if you do not enjoy the state of affairs—how would we ever advance? The passion for improving the way we treat each other should not be met with such animosity.

Sometimes the argument about leaving is based on the idea of a social contract: since you live here, you have agreed to the terms and you must pay without complaint. Such a contract does not exist, neither today nor in the times when robbers from Torsätra, Uppland, came to demand gjald from Gotlanders. The concept of contract rests on a voluntary agreement between the signing parties. The social ”contract” is a pure creation of vivid imagination, and there is no trace of anything voluntary, nor of any agreement, parties, or signatures.

The other objections are even more strange for someone who does not accept the perpetrator’s description of the crime. Is it not theft because the thief spends some of the loot on things you like?

Financing anything by means of theft is counterproductive even on the odd chance that you like whatever the thief uses the money on. Besides, if you really liked those goods and services, how come you had not already purchased them at the time of looting?

As humans we need to be left in peace to conduct voluntary action in order for value to be created. Force, coercion, and thievery function as guarantees that the wealth that conditions of liberty would create[7] never comes to be.

Theft-financed healthcare will eventually become lousy healthcare. Given some more time it will, due to the unforgiving laws of economics, develop into something much worse.[8] The same goes for all things being financed through the means of taxation. Why do you think the roads are so jammed and in such poor condition? How come, after being compelled to spend a decade in public education, many still cannot read, write, or do math at a decent level? Have you noticed how theft-financed defense either does not really defend the people (as in the US), or is so useless that the people cannot count on it for defense at all (as in Sweden)?

All human association that is not founded on consent means that a crime is being committed. If you want something, you should pay for it yourself. If you want something to exist in common, you should utilize dialogue and arguments to convince others to join you in financing it. To use violence, or the threat of violence, to force others is not a civilized way to conduct yourself. And what is wrong cannot become right if done by proxy, nor because a majority votes in favor of it.

Stealing is wrong. Uffir and his wife, Ylva, knew this. Whether Husbjörn and his brothers, Skuli and Folki, knew it remains unknown. But they knew enough about other people’s views on the subject that they chose to call it gjald.

via Mises Institute

1. The Torsätra runestone: Wikipedia, s.v. “Uppland Runic Inscription 614,” last modified Mar. 4, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uppland_Runic_Inscription_614.

2. Gustav I of Sweden (reigned 1523–60). See Wikipedia, s.v. “Gustav I of Sweden,” last modified Aug. 13, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustav_I_of_Sweden.

3. Nils Dacke, Swedish yeoman and rebel (died 1543). See Wikipedia, s.v. “Nils Dacke,” last modified Aug. 13, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nils_Dacke.

4. Timothy Taylor, “How Milton Friedman Helped Invent Income Tax Withholding,” Conversable Economist (blog), Apr. 12, 2014, https://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2014/04/how-milton-friedman-helped-invent.html.

5. Bitbutter, “You Can Always Leave,” Apr. 15, 2013, YouTube video, 11:30, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fasTSY-dB-s.

6. Ergo decedo is Latin for “therefore leave”: Wikipedia, s.v. “Ergo decedo,” last modified June 21, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ergo_decedo.

7. Peter Strömberg, “Vad friheten må skapa” (roughly, What only liberty can create), Samarbetet Cospaia (Collaboration of Cospaia, website), Aug. 25, 2020, https://cospaia.se/2020-08-25/vad-friheten-ma-skapa/.

8. Per Bylund, “Därför kan offentlig sektor inte fungera” (roughly, Why the public sector can’t function), Samarbetet Cospaia (Collaboration of Cospaia, website), Aug. 13, 2020, https://cospaia.se/2020-08-13/darfor-kan-offentlig-sektor-inte-fungera/.

The post Taxation and Theft, Viking Style appeared first on Sovereign Nations.

– Sovereign Nations