The Democratic National Convention should’ve been some of the best days of Justin Giboney’s life.

His first steps into politics had been wildly successful: almost on a whim, he joined a team working to help Kasim Reed rise from a little-known politician to the mayor of Atlanta. The election landed Giboney a job as city attorney, and in 2012, he was chosen as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention where Barack Obama would be nominated for the second time.

“I was excited to be there, with all the pomp and circumstance,” he told TGC. He’d seen how hard work could make a difference in a local campaign, and he was eager to be part of the larger movement.

“Then there was a voice vote on whether to keep ‘God-given rights’ in the platform,” Giboney said. “It was clear the folks who wanted it out were way more excited.”

That made him pause, because Giboney loves the Lord. He wasn’t sure about throwing in with a political party that couldn’t wait to kick God out.

“Then the gay marriage issue came up, and I thought we’d vote on it, and that would be that,” he said. “Every day it was supposed to come up. Every day I thought, ‘Okay, well, we’ll vote tomorrow.’ Then on the last day, the chair of the Georgia Democratic Party said, ‘Hey, because there were no objections, we’ll put it into the platform.’”

Giboney knew right away that the state party leader was avoiding a vote because more traditional African Americans might have voted against it. “We were kinda forced into it,” he said. He found the move disrespectful, not only to the delegates but also to the people who voted for them.

“I went home disillusioned,” Giboney said. But the former college football player is not one to sit around. He started looking for anybody he knew who was a Christian and interested in politics. They met together at his church, encouraging one another to be God-fearing in a field that runs on fear of man.

Two of those people were TGC Council member John Onwuchekwa and hip-hop artist Sho Baraka. “John, especially, gave me a depth of theological perspective I didn’t have before,” said Giboney, who is now enrolled at Reformed Theological Seminary (RTS) in Atlanta. “I started to realize I had to be deliberate about applying biblical principles to the type of political actor I am.”

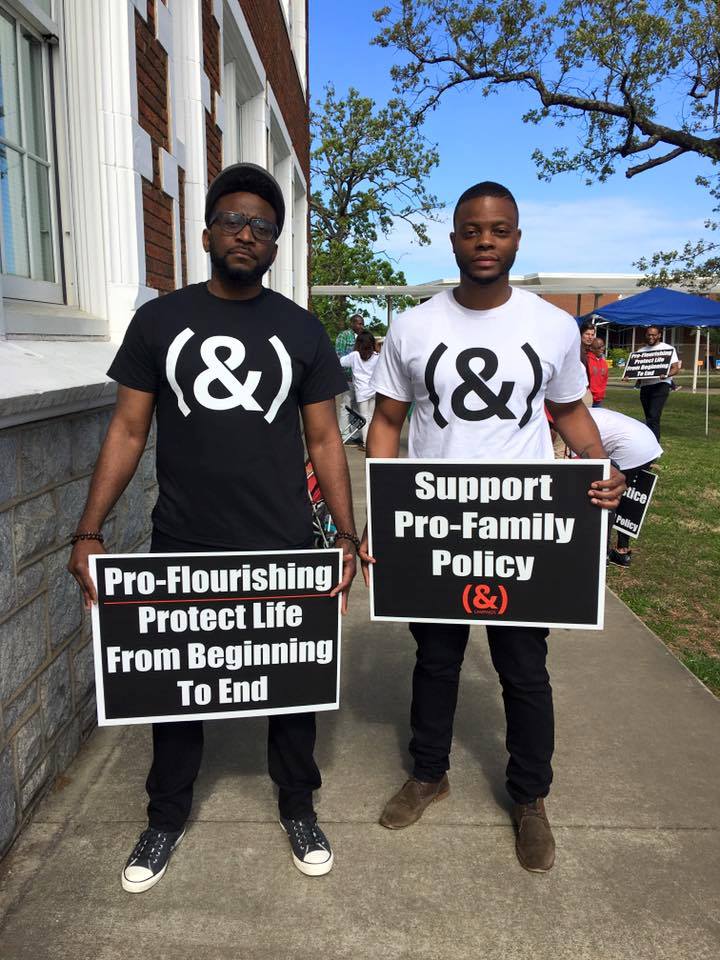

In 2015, Giboney, Baraka, and Angel Maldonado started the AND Campaign, which aims to connect conviction and compassion. The organization sets out a platform you won’t find at either political convention—anti-abortion, pro-social safety nets, pro-family, pro-criminal justice reform. The point isn’t to endorse legislation or candidates or judicial decisions—AND doesn’t do that—but to “bring Christians of both parties together on those issues.”

The AND Campaign leans left, but has increasingly become a space for Christians dissatisfied with both political parties. In 2017, Giboney quit his day job to work full-time for AND. In 2020, AND launched a Prayer (&) Action justice initiative and raised $1.3 million for low-income churches to get through the COVID crisis. In July, Giboney and coauthors Michael Wear and Chris Butler released Compassion (&) Conviction: The AND Campaign’s Guide to Faithful Civic Engagement.

“Justin has blown up in the last year and a half,” AND executive board member Kori Porter said. In the last three months, AND has gained 40,000 Instagram followers and doubled its local chapters from five to ten. “I can’t speak enough about his character and his godliness—what he espouses is exactly how he lives.”

“Justin is uniquely equipped with a particular set of skills,” said Karen Ellis, director of the Edmiston Center for the Study of the Bible and Ethnicity at Reformed Theological Seminary. She met him back when the ideas for AND were just beginning to churn around in his head. “Justin’s intellectual honesty, teachability, and willingness for self-examination, and his academic, political, and scriptural humility––qualities often missing among those who pursue theological innovation––struck me even then.”

Growing Up

Giboney grew up in Denver, where his dad worked for the city water department and his mom worked for the regional transit system. A serious kid, he liked to win at sports and read political biographies.

Both his father and his father’s father had wanted to practice law but never had the opportunity, so from childhood, Giboney knew what he was going to do when he grew up. In 1999, he graduated from high school and headed to Vanderbilt University on a football scholarship; four years later, he enrolled in law school there.

Giboney ended up in medical malpractice defense in Atlanta. Everything was just about perfect: he was making good money doing the job he was born to do, dating a beautiful girl, and hanging around with a group of guys he’d known from law school. “I really fed on it, making my way in that space,” he said.

The only thing wobbling was his faith. He’d been raised in a Christian family—his grandfather was a preacher—but “when I went to college I didn’t have an apologetic,” he told TGC. In his liberal theology classes, he “just didn’t have any answers” to the challenges to his faith. He was told that “as long as you’re a nice person and do some community service, you can do what you want to do.”

For a young man making his way through school and football and girls and a lucrative first job, that’s an easy message to hear.

Political Rush

When Giboney and his friends hung out, they discussed two things—sports and politics.

“We’d just talk about what was going on politically,” he said. “Then one day we were like, ‘Why are we being so academic about this? We’re just sitting here talking. But there’s nothing stopping us from getting involved.’”

So they did, in the style of recent law grads: They researched each of the six Atlanta mayoral candidates, writing each other memos about what they found. They argued about which candidate had better qualifications. And then they picked one—Georgia senator Kasim Reed—and got to work.

“He was at like 1 percent in the polls,” Giboney said. Undeterred, “we were out there knocking on doors.” The friends kept showing up—handing out campaign literature, putting up signs, making phone calls, setting up for rallies. They showed up so consistently that eventually they were helping Reed prep for debates and speaking on his behalf at events he was unable to attend.

“I wasn’t trying to change the world,” Giboney said. Initially, at least, his motivation was less altruistic.

“I remember the first game after I graduated, when I realized I would never play football again,” he said. “It was painful. I’d been looking for something that gave me that same rush.”

He found it in politics—the same hard work and intense focus could lead to similar wins. But unlike college football—which mandates that pants must cover the knee, that at least three officials must enter the field 90 minutes before kickoff, and that memorial patches can’t exceed 2¼ inches—rules in politics are nowhere near as precise.

“I learned very early on that you move up by being the person who does stuff other people don’t want to do,” Giboney said. “Sometimes it was getting up early in the morning—being there when no one else was. It could also mean being willing to do underhanded things, and not necessarily treat opponents fairly.”

He remembers being the first troll on the message boards of the Atlanta Journal Constitution, typing comments—“true, false, whatever we had”—to throw shade on the other side. “I’m very serious about civility now, but I wasn’t at the forefront of always doing that,” he said. “I started off as—hey, whatever you have to do to win.”

In the end, Kasim Reed squeaked out a win in the Atlanta mayoral race in overtime—beating Mary Norwood by less than 1 percent in a second run-off election. Reed gave Giboney a job as an attorney for the city.

Connecting Faith to Politics

The rush wore off. After a year or two, Giboney was frustrated with his freewheeling lifestyle, knowing he was hurting those around him and not living the way he should.

So he started going to church. He got engaged to his girlfriend. And he began the slow process of trying to connect his faith to his politics.

“It became less easy to get on a message board and say anything,” he said. Once, after helping with a successful campaign, he spotted the defeated opponent and asked how she was doing. “I’m doing all right, now that you’re not on my back anymore,” she told him.

I had to be deliberate about applying biblical principles to the type of political actor I am.

“I could see her in face that [the comments] had impacted her,” Giboney said. “I was like, Oh, man, what am I doing?”

He didn’t want to leave politics altogether, but he did want to find a better way. “I didn’t see a lot of examples of Christian politicians pushing their party to be more Christian,” he told TGC. “I’m sure they were out there, but I didn’t have that clearly in front of me. I had some great mentors who did the right things, but the explicit faith connection wasn’t clear to me.”

Around that time, Giboney heard of a new church plant called Cornerstone opening up on the under-resourced West Side. He sent a donation and a message: “I’m a local Christian who would help your church’s launch in any way I can. Please let me know how I can serve.”

One of the planting pastors, John Onwuchekwa, wrote him back: “Let’s find a time to grab coffee.”

Onwuchekwa introduced Giboney to Reformed theology (“I didn’t even know about those labels”), to C. S. Lewis, and to G. K. Chesterton. “We didn’t agree on everything, but it was very helpful to get a different perspective,” Giboney said. “I had never put my theology into an apologetic before.”

He started to understand that “we have to apply the biblical principles to everything in our lives. That was a blind spot––a disconnect––until that moment.”

Giboney kept feeling his way forward, forming a Bible study at his church with eight to ten Christians (including Onwuchekwa) to talk faith and politics. They studied Daniel, who didn’t compromise his convictions, and Paul, who used honest but persuasive rhetoric to get across his message.

“Justin is really intentional,” AND Campaign co-founder Sho Baraka said. “When I first met him, he asked me a question like, ‘Do you think there is a Democratic leader today we can trust with biblical values?’ He gave me this look like he’d just dropped an essay assignment on me and expected three pages in the next 20 minutes.”

Baraka laughs, but knows there was a reason behind Giboney’s intensity. “He needed kindred spirits. He didn’t trust a lot of people in politics.”

As more people gathered, “we felt emboldened,” Giboney said. “We knew we weren’t alone.”

He remembers a Democratic meeting decrying the Supreme Court’s decision to allow closely held companies such as Hobby Lobby to claim religious exemptions—in that case, from controversial forms of contraception.

“The Democrats were pulling out their hair and going crazy,” Giboney said. “I’m an attorney—I knew it wasn’t what they said it was.” He did some research, and at the meeting, he and his friends began raising their hands to offer corrections to the meeting leaders.

“By the end of the meeting, people were asking us more questions than they were asking the leaders,” Giboney said. “They were surprised that Christians came and were better informed.”

Giboney’s group started to put the pieces together: since God is sovereign over everything, that means no political decision or policy is left out. It all matters to him.

And by showing up with information and grace, emboldened Christians could influence opinions.

AND Campaign

In December 2015, Giboney, Angel Maldonado, and Sho Baraka founded the AND Campaign.

“They didn’t take up the language of preexisting movements, but created their own slogan and their own concepts,” said Ellis, who watched the plans come together over countless conversations. She liked that: “We should be a people who are practicing politics based on the life, death, resurrection, and glorification of Jesus. Our politics should be based on the story that defines us.”

We should be a people who are practicing politics based on the life, death, resurrection, and glorification of Jesus. Our politics should be based on the story that defines us.

So instead of taking language from either political platform—“both sides frame the issue to fit incomplete or dishonest narratives,” Giboney would later write with Wear and Butler in Compassion & Conviction—the AND leaders wrote their own. Their poverty and economic mobility statement, for example, supports strong social safety nets, the dignity of work, and public-private partnerships to serve those in need. Their immigration-reform statement supports both a government’s responsibility to monitor its borders and also the welcoming of refugees.

“The Bible played a huge role,” Giboney said. “We had to be honest about what it spoke to directly, and where we could disagree.”

That’s why the AND Campaign opposes abortion and supports religious liberty, but doesn’t have a position on tax rates or minimum wage.

From early on, Ellis thought AND Campaign had the potential to teach the church to think more critically about civic responsibilities. She appreciated Giboney’s law background and political training. And she really liked his ability to critique the Democratic Party he leans toward.

“It shows a person is willing to slay their flesh and lay down their idols,” Ellis told TGC. “That’s one key to keeping an idea or movement from becoming an idol—that willingness to do self-assessment.”

In the hyped-up polarization of today’s politics, many people—even Christians—are looking to elected officials or laws for salvation from sins such as racism and abortion. “We substitute culture for Christ,” Ellis said. “We are bent toward creaturism, even in the church. We want to define the world based on us.”

Depending on your political party to set things right is as easy as worshiping a golden calf you can see versus a God you can’t.

So Giboney developed a way to check himself and his team.

Compassion (&) Conviction

He’ll start with an issue—abortion, or gay rights, or immigration, or something that’s been in the news or the courts. And then he’ll ask his team: Where is the compassion?

In the case of a woman considering abortion, the compassion is for her felt hopelessness—the poverty or abuse or social lies that tell her ending her pregnancy is her only option. Giboney’s team will discuss the way she likely views God, and her options (or lack thereof) for childcare or education or a higher-paying job. They try to see why she sees things the way she does.

Depending on your political party to set things right is as easy as worshiping a golden calf you can see versus a God you can’t.

And then Giboney will ask: What’s the truth? What does the Bible say?

Answer: God has formed both the woman and the child in her womb (Ps. 139:13–16). Taking an innocent life is wrong (Ex. 20:13). And ending her pregnancy won’t solve her problems; it will just add distress and guilt to them.

So real compassion for a pregnant woman in a desperate situation isn’t just preventing a Friday afternoon abortion. It’s also connecting her with a pregnancy center, with a local church, with a community of believers who will love and care for her practical needs. It’s finding a way for her not only to keep her child, but also to know Jesus, to find steady income, to see hope for the future.

By moving past face-value compassion to a deeper conviction, Giboney and his team can see the way to a thicker and more robust mercy.

“We separate [compassion and conviction] to understand them, and then bring them together, because that’s how the gospel has it,” Giboney said. “They’re not separate. They feed each other.”

‘Not My Tribe’

The AND Campaign’s first full year was 2016, when America’s growing political divide felt sharp and angry. When he’d explain AND’s vision, “Christians loved it,” he said. But his political buddies were confused—was he trying to set up a left-wing rivalry? Why couldn’t he just throw his weight behind the Democratic Party?

“They didn’t have the moral imagination to see it could be different than the way it is right now,” Giboney said. He didn’t want to grow discouraged, so he limited his conversations about AND to other believers. “You can’t explain it. You have to show them.”

In 2016, Giboney ran again for a delegate spot at the Democratic National Convention. During his speech, he plugged caring for the widow and fatherless, helping those in poverty, protecting the unborn, and holding to biblical standards of sexuality. He won by more than 100 votes, but one of his mentors thought he had committed political suicide.

“I wasn’t surprised that was said,” Giboney said. “I had counted the cost. I was like, ‘Hey, I gotta do it.’” Though he was a delegate for Hillary Clinton, he didn’t support her and went to the convention as a “protest delegate.”

“I think it’s clear that this is not my tribe,” he said. You could say he’s in Democratic circles, but not of them.

Ellis compares him to Daniel. “When the political party you oppose comes to the throne, you want a Daniel at the table who can represent your interests to the people who are against you. You want Daniels in all the political parties, seeding policy with ideas that are life-giving and not life-destroying.”

Faithful Framework

In 2016, Giboney spoke for the first time at the Legacy Disciple conference. In 2017, he presented at the Just Gospel Conference. “I went from a couple speaking engagements in all of 2016 to now more than three or four a month,” he said.

In 2018, local chapters of AND were started in Atlanta and Chicago, followed by Dallas, New York City, and Washington, D.C.

Then came the summer of 2020. AND’s Instagram followers shot up from around 15,000 to nearly 56,000. So much interest was expressed that by early next year, local chapters will start in Charleston, Nashville, Memphis, Houston, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Kansas City, Raleigh, and Denver.

This doesn’t mean the growth has been easy, and AND has taken plenty of hits from people on social media accusing them of hypocrisy, supporting riots, and leaning too far left. Offline, AND gets pressure to unequivocally support or reject organizations like Black Lives Matter or the Democratic Party.

“We’ve had some tense experiences with chapters who felt we were either too left or too right,” Baraka told TGC.

And everybody always wants AND to tell them who to vote for.

“We don’t believe there is one candidate all Christians need to vote for in our elections,” Wear said. “We’re more focused on ensuring that Christians, no matter who they vote for, are voting as Christians with the compassion and conviction of Christ.”

Giboney wants AND to be an example of how to engage politics in a biblical way.

“We want to bring Christians of both parties together on biblical issues,” he said. “Ultimately, I want Christians to look at us and say, ‘Oh, that’s what a faithful framework looks like.’”

Read More

The Gospel Coalition