When Jenny Mallow’s father died from starvation, she was glad.

“I felt like, ‘Good for him,’” she said. “It’s better than if they took him to torture and kill him.”

And they would have, eventually. Jenny’s father was a Cambodian soldier when the Khmer Rouge regime came to power in 1975. Prime minister Pol Pot wanted the country to have a fresh start—as in, to return to agrarian living and evolve into a communist utopia. His soldiers forced those in the cities to collective farms in the country, and then tried to clean Cambodia’s slate by killing everyone involved with the former government (including soldiers), everyone who’d had any dealings with foreign countries, and everyone who was educated. Some were killed just for wearing the modern invention of glasses.

Cambodia had a population of 7.5 million when Pol Pot came to power. Four years later, the Khmer Rouge had killed an estimated 2 million people, most famously in “killing fields,” in which so many bodies were piled that clothing and bones still emerge from the dirt after a heavy rain.

Jenny survived to see the Vietnamese invade Cambodia in 1979, booting Pol Pot out of power. But Jenny’s mother didn’t trust that things would improve under another Communist regime. She took her children—as many of the eight as she could find—and headed for the refugee camps in Thailand. Several years later, they immigrated to Chicago.

Back in Cambodia, the aftermath was not easy. Though the population has grown to nearly 17 million and economic growth has been an encouraging 7 percent to 9 percent a year, poverty and political corruption remain high. Insulting the monarchy can be punished with up to five years in prison, 4.5 million live just above the poverty line, and 3 million still lack access to safe water.

Jenny was fortunate to be in the United States with most of her family, learning English and working to help support her mother. In 1989, she met a missionary at her church in Chicago. In 1990, she married him.

And then in 1991, she moved with him to Cambodia—the place where most of her relatives, including her father, starved to death. (No one knows how her sister died.)

“I think God changed my heart,” she explained to TGC. “I had a heart to share about Jesus.”

When the Mallows landed in Cambodia, there were an estimated 2,000 Protestants. Over the last 30 years, in a country that knows the cost of manmade utopian efforts, the number has jumped to more than 300,000. The annual rate of growth has been a sizable 8.8 percent.

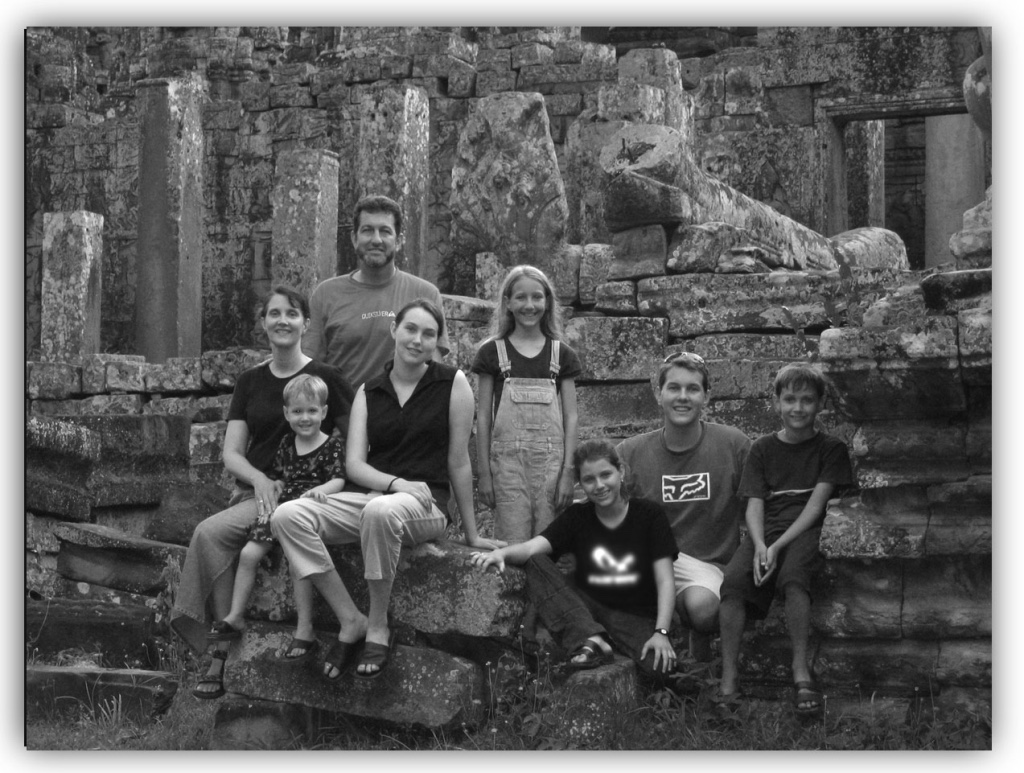

The Mallows work with tribal people in the northeastern part of the country. So does missionary J. D. Crowley, who along with other missionaries has seen 3,000 people come to Christ and 70 churches planted since 1994.

“When we can catch our breath, we just shake our heads and think what a privilege it has been to watch God do what he’s done up here,” he said. “It’s a great privilege—praise God.”

Holocaust

Cambodia is in Southeast Asia, pressed between Vietnam and Thailand. The first Protestant missionaries arrived around 1923, when the country was still a French colony. But just 40 years later, all foreign missionaries were expelled and nearly all churches closed when relationships with the West deteriorated over Cambodia’s neutral stance on communism.

When the American-Cambodian relationship warmed in 1970—the United States would provide more than $1.5 billion in military and economic assistance as the Cambodian government tried to fight off the communist Khmer Rouge—churches and missionaries were allowed to operate. The people were receptive: in 1972, World Vision president Stanley Mooneyham spoke at two evangelistic crusades, and World Vision recorded a combined 4,700 decisions for Christ.

They were probably converting from Buddhism, which had been the state religion since the 13th century, and which 95 percent of the population followed. “My grandma would go to the temple four times a week,” Jenny remembered.

But Pol Pot didn’t want religion on his clean slate. In four years, the number of Buddhist monks and novices plummeted from around 65,000 to fewer than 100—most of whom had fled the country. Of the 10,000 estimated Protestant Christians, only a few hundred were left. Just six of the 17 Cambodian pastors and evangelists had survived—two because they’d been outside the country when the Khmer Rouge took over.

In 1979, Vietnam toppled Pol Pot and took over Cambodia’s government. But the idea of another Communist regime wasn’t reassuring, and about 630,000 Cambodians fled the country between 1979 and 1981. That included the only three Protestant pastors left alive. “Under their ministry in the [refugee camps in Thailand], thousands of refugees have come to faith in Christ,” Christianity Today reported in 1981.

Two of them were Jenny and her mother, who spotted a church in their refugee camp while on their way to the Buddhist temple. Jenny was immediately hooked by the stories (starting with David and Goliath) but it was her mother—who could remember asking “Who made the stars?” and her grandmother’s “I don’t know”—who came to Christ first.

“Observers reported that in 1980 there were more registered Khmer Christians among the refugees in camps in Thailand than in all of Cambodia before 1970,” researchers in the Library of Congress reported in 1987.

Return to Cambodia

In the late ’80s, Kreg Mallow arrived at the refugee camps with a dental school diploma and a heart for missions. “I couldn’t have told you if Cambodia was in Africa back then,” he said.

After a year, he took a hiatus in Chicago, where he started attending the Cambodian congregation that met in his Baptist church. There he met Jenny, who had been in the United States for nine years. He wanted to marry her, but he also wanted to work in Cambodia, and she “had no plans to go back,” he said.

“I knew he had a heart to be a missionary,” Jenny said. She didn’t want to leave her family, but she also knew God had sent her Kreg.

“The Lord changed her heart,” Kreg said.

When Jenny told her mother she was going back to Cambodia, she emphasized that she’d be able to check to see if any of their relatives were still alive. Jenny’s mother, who trusted Kreg to keep her daughter safe, gave her blessing.

In 1991, just as the country was opening up, the newly married Kreg and Jenny arrived to help World Concern restart a dental school in the capital and train nurses to do dental care in rural areas.

A few years in, they began training nurses in the northeastern part of the country, in an area called Ratanakiri. The land is home to lush forests, waterfalls, and tribes of people so rural and uneducated that Pol Pot held them up as examples of communism in its purest form.

“We fell in love with the place,” Kreg said. “It was a completely unreached province. They’d never had missionaries there. We were like, ‘Wow, we should stay here longer.’”

They couldn’t—the Mallows had to return to Phnom Penh. But they’d be back.

Power of Unity

During the few months the Mallows were in Ratanakiri, the first missionary family arrived. J. D. Crowley was a pastor and a linguist sent out from Evangelical Mission to the Unreached. He got to work learning Khmer—Cambodia’s main language.

Before long, other missions organizations—OMF International, Christian and Missionary Alliance, Wycliffe Bible Translators—arrived to help.

“We had tremendous unity—amazing unity,” Crowley said. “One of the things we prayed constantly was that God would keep the wrong people from coming.”

They prayed for people who believed in the inerrancy of Scripture, the Apostles’ Creed, the Nicene Creed, and a creation-to-Christ arc of Scripture.

“God answered,” Crowley said. “The methodological and doctrinal unity really added to the power of the gospel up here.”

The missionaries—at times as many as 20 church planters, relief workers, linguists, and Bible translators—had a lot to do. They studied six tribal languages, slowly working out alphabets for each one. They taught people to read. And then they translated the Bible—today, two of those languages have nearly complete New Testaments, and three others are in the process.

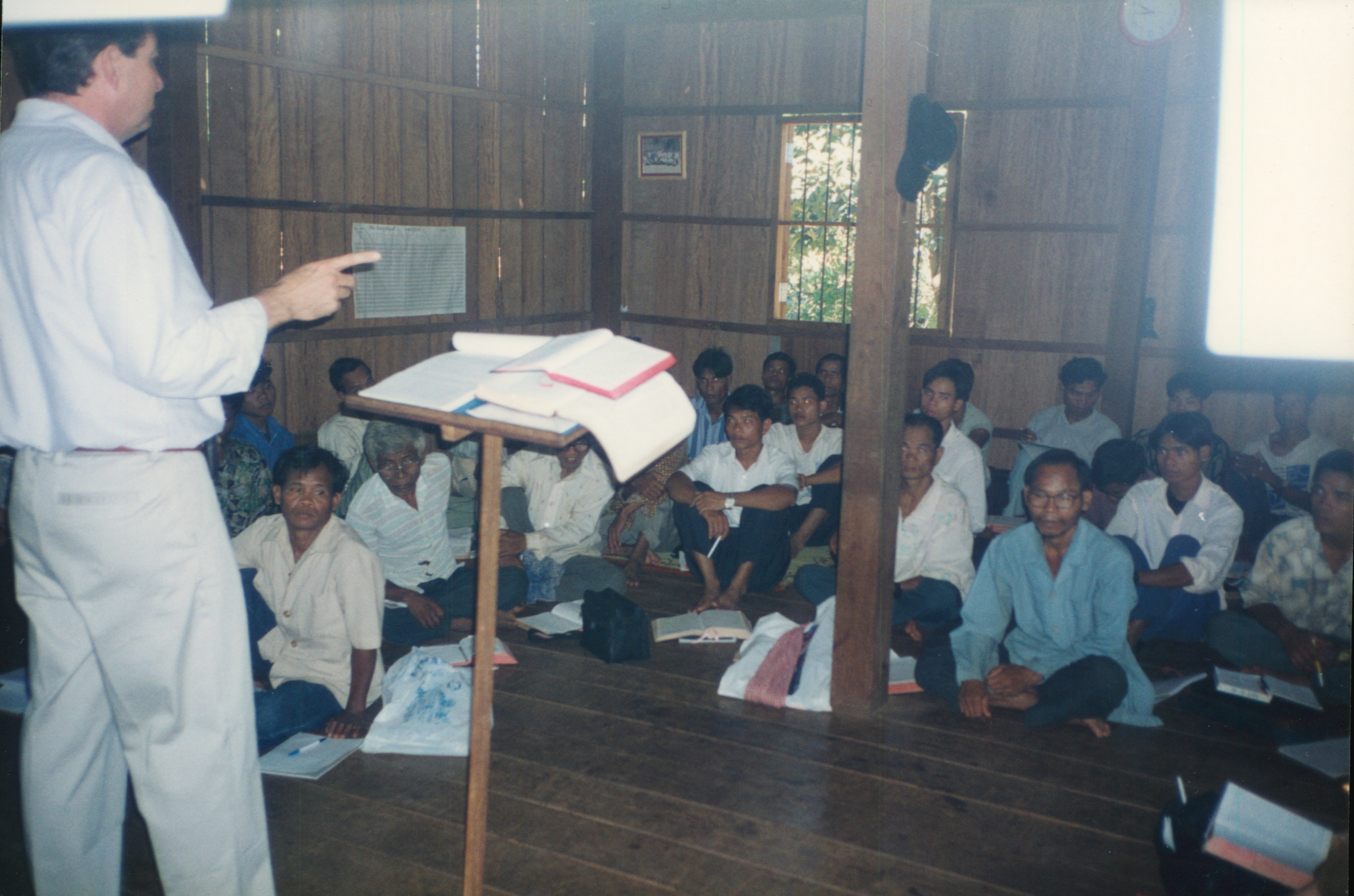

Along the way, they evangelized, said Kreg, who gave up dentistry to do literacy work in Ratanakiri, and then literacy work for full-time evangelism. They didn’t start with sermons on Paul’s letters or on the so-called four spiritual laws. The people couldn’t even understand the questions: Who is God? What does that mean? What does sin mean?

Instead, the missionaries told stories. They told the story of God creating the world (and the introduction of sin). They told the story of Abraham (and God’s concern for the nations). They told the story of Moses (explaining the law and again defining sin). They told about Israel falling away over and over again (and needing a Savior). And then they told the story of Jesus.

It was basically like reading the Jesus Storybook Bible. With every story connecting to the larger Story, the foundation was so understandable and solid that “when we finally did teach biblical theology to the pastors as a theological course, it wasn’t that hard for them to get what was going on,” Crowley said.

After the first few Bible study groups were started, word spread quickly—almost too quickly.

“They’d be like, ‘I have a cousin in the other village who wants to become a Christian,’” Mallow said. “But I learned early that ‘they want to become a Christian’ really meant ‘they’ve heard about God and want to stop being an animist and follow God, but don’t know what that means.’”

Animism to Christianity

In many ways, Christianity speaks the language of animism.

“Both believe in a Creator God, although [animists] don’t know much about him,” Crowley said. “Both believe there are evil spirits who want to hurt us and control our lives. They just don’t have the right solution to the problem, which is loving relationship with the Creator God through faith in Jesus Christ.”

To appease the spirits, Ratanakiri tribes make sacrifices. For serious problems, such as a major illness, they may kill a chicken, then a pig, then a water buffalo. “They can give up a life savings over Granddad’s cancer,” Mallow said. “And then why isn’t it working? It’s frustrating for them.” (“It’s very much like if once or twice a year you had to smash your car with a sledgehammer—it keeps them perpetually poor,” Crowley said.)

So news of a stronger God, who doesn’t require animal sacrifices, is really good news. “There are still so many questions—they don’t understand anything about sin or guilt,” Mallow said. “They start hearing that he loves them and died for them on the cross, and they’re trying to figure out why he had to do that.”

Not every seed takes root—some people leave the church when Granddad still dies of cancer, or when a church leader sins, or when the Christian life calls for sacrifice. Sometimes villages, worried about repercussions from the spirits, grow angry with new Christians who refuse to participate in communal sacrifices.

“After a year or two, that seems to calm down,” Mallow said. “I think they find that, ‘Hey, everybody isn’t going to die.’”

“In the worst days of persecution—about 20 years ago—I told everybody, ‘Someday they’ll ask you to be their village leaders,’” Crowley said. “I’m not a prophet, but it’s happened. Many Christians are now village leaders, because they’re trustworthy and wise and kind and good.”

Center for Christianity

Crowley remembers a Cambodian army general telling people that Ratanakiri was not going to become a center for Christianity.

“When I heard this, about 15 years ago, I said, ‘It’s too late. It’s already happening,’” he said. “What a privilege to watch God do it.”

In general, the pushback has not been terrible from a government that still wavers between democracy and one-party rule. “To be fair,” Crowley said, “Cambodia has one of the highest degrees of religious freedom in mainland Southeast Asia.”

“At the beginning, the provincial head of religion went on TV and told people not to listen to me, claiming I didn’t have the right permissions to be up here,” Crowley said. “That was a little embarrassing. . . . But more recently, a member of parliament from this province called the producers of the nightly Christian radio broadcast to say, ‘You’re using the old tribal style of music for your Christians songs. This is wonderful. Keep it up.’”

The growth of Christianity in Ratanakiri is not only broad, but also deep. The creation-fall-redemption approach gives people a new framework that makes sense.

“Because of that, most of the converts up here have a really good grasp of the entire Bible and what it’s all about,” Crowley said. “There are a lot of local people up here who can share the gospel in a clear and lucid way from creation to Christ.”

In the beginning, as baby churches formed in different villages, they chose leaders to go to the provincial center to learn the Bible in Khmer from Crowley and the other missionaries.

“That was the beginning of the Bible school movement,” Crowley said. The missionaries began to offer classes that fit around the agricultural schedule: leaders could learn, go home to teach, come back to learn, and repeat.

It wasn’t without troubles—sometimes, a leader would have major sin revealed in his life and have to step down for a while. Sometimes a leader would fall away altogether. But God was always raising up more. A few years ago, the local pastors agreed to take over the training of new leaders in their own tribal languages—all completely funded by the local churches.

“When you remember that the indigenous minorities have been looked down upon since time immemorial, and that most of these leaders have an average of a third-grade education, it’s astonishing that they’re now running their own successful Bible training programs for more than 200 students in four languages,” Crowley told TGC. “You can imagine the positive effect this has had on their self-perception and their faith in God. All who see it give praise to the Lord.”

Not Slowing Down

Over the last 26 years, Ratanakiri has gone from zero churches to 70.

“At this point, we’re at the fourth or fifth generation of leaders,” Crowley said. “We’re in our fifth or sixth generation of church planting.”

In the rest of Cambodia, the number of Christians has risen to more than 300,000, according to the Joshua Project. With an 8.8 percent evangelical growth rate—compared to a global evangelical growth rate of 2.6 percent—“it’s one of the faster-growing regions in the world,” Mallow said.

“I didn’t know any Christians at all when I was growing up,” Jenny said. “I thought it was a white people’s religion. Now God has changed a lot of people’s minds.”

“Christianity spread so quickly up here—we were always behind what the Holy Spirit was doing, trying to play catch-up,” Crowley said. “And it doesn’t seem like he’s slowing down.”

Read More

The Gospel Coalition