When Vanita Thomas met her future husband, Peter, for the first time, she asked if he would be interested in adopting a child with her.

It wasn’t a premature question—their marriage was arranged, and their first meeting was meant to see if they were compatible. Potential future children were important to discuss. But it was a weird question, because adoption was uncommon in India, where both were born. (“People believe that God opens and shuts wombs, so if you adopt, it means you didn’t have enough faith,” Vanita said.)

But Vanita was determined. “Growing up, my school took us to one of Mother Teresa’s children’s homes in Bangalore to visit the orphans,” she explained. “I remember begging Mum and Dad to take one of those kids home. They said that they already had three kids, and anyway, it’s wasn’t something normally done in India.”

But she didn’t forget about it. Years later at their first meeting, she asked her future husband what he thought about adopting. Peter, who had just finished reading about God spiritually adopting believers into his family in J. I. Packer’s Knowing God, agreed immediately. Five years later, Peter had finished graduate school, the couple had immigrated to New York, and Vanita had lost a pregnancy. It’s time, they thought.

“At that point, we heard about a situation in India,” she said. That’s a gentle way to put it: a mother had killed herself and her alcoholic husband was unfit to care for their children. The two older girls were taken in by relatives, but the youngest had nowhere to go. Peter and Vanita felt God directing them to adopt the child.

“At that point, we didn’t know if it was a boy or a girl, nor the age of the child,” Vanita said. “We just wanted to give this hurting child a forever family. And we believed that we could trust God, and that with love and fresh air it would all be okay.”

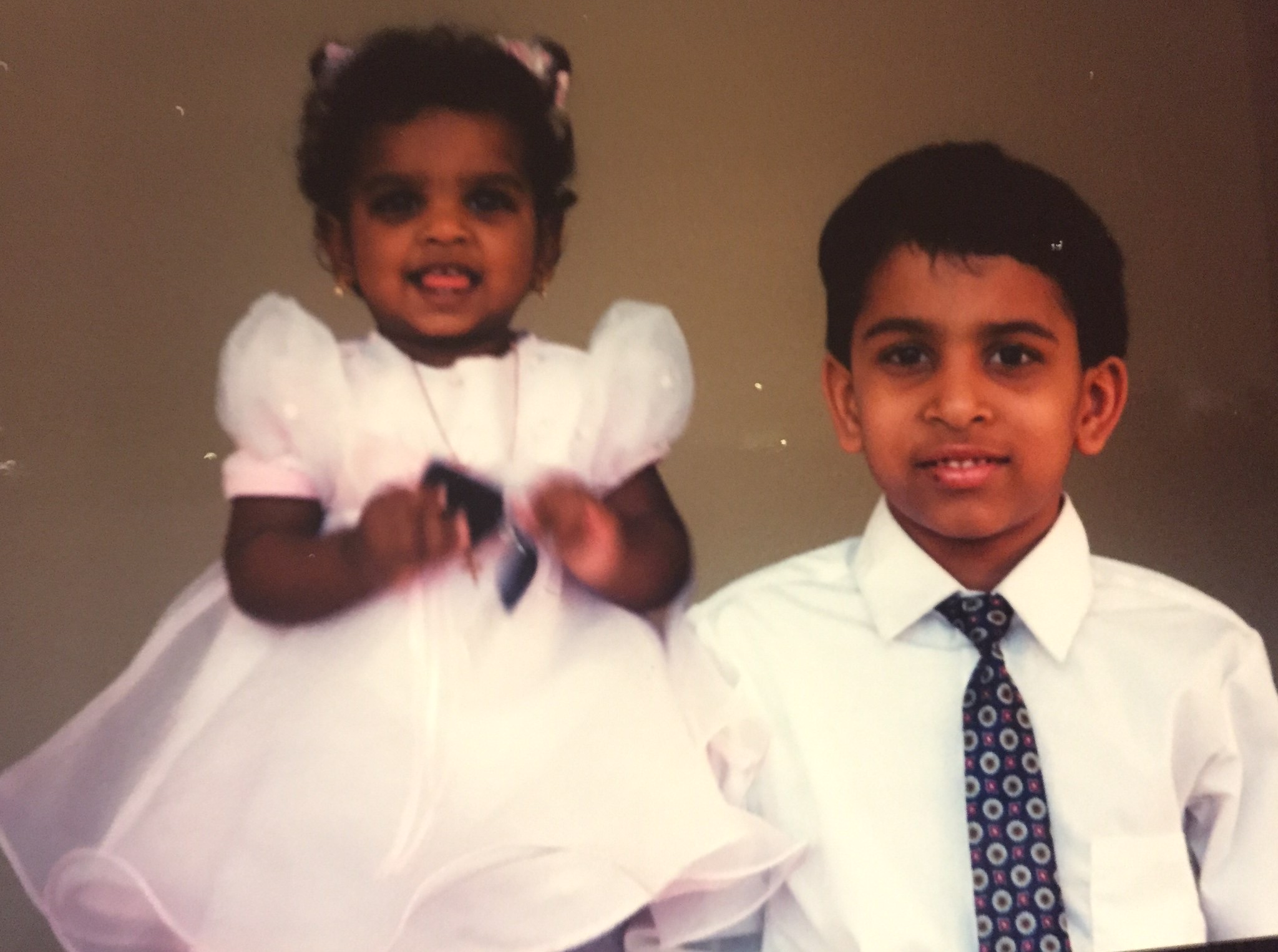

The boy—Sandeep—was one of 13,600 children adopted from overseas in 1997. He was on the early edge of an international adoption bump that started in the mid-1990s and peaked in 2004 at nearly 23,000. Domestic adoptions, too, were on the rise.

When you mix the difficult questions of identity along with the impact of early deprivation and trauma, that can make it a really difficult season of life for both child and parent.

“There was really a significant reawakening of the historic Christian role of caring for orphans in the mid- to late-2000s,” Christian Alliance for Orphans (CAFO) president Jedd Medefind said. “This included the adoption of many children coming from orphanages who’d experienced significant deprivation or trauma.” Those kids are now hitting their teen and early adult years.

For Sandeep, love and fresh air weren’t enough. In high school, he fell behind in his work and lashed out at his parents. Nothing they said or did softened his anger at the life he’d had. His constant rebellion and rage were so exhausting that after a while they needed respite care and sent him to live with an uncle for a school year.

“I think God took us through this process to smash all our idols,” Vanita said. “He was saying, ‘It’s not in your strength you’re going to do this, but in mine.’”

Sandeep’s struggles, while unique to him, are a common theme in adoption circles. His younger sister, who was adopted at the same time, has wrestled with it her entire life.

“What we’re seeing now is a natural progression,” Medefind said. “When children move into adolescence, a lot of chemicals are surging through their bodies and they’re wrestling with their identities. When you mix the difficult questions of identity along with the impact of early deprivation and trauma, that can make it a really difficult season of life for both child and parent.”

Books have been helpful—Karyn Purvis’s The Connected Child has become an adoption classic—but “often the need outstrips the resources,” Medefind said. The demand for more thought leadership is enough that CAFO is developing plans for a center to provide a hub for the best available research, resources, and gospel-centered guidance.

With more than 20 years of experience, the Thomases are some of those resources, offering hope and advice for those coming behind them.

Fundamental Brokenness

“In many ways, adoption wades into some of the most profound brokenness in our world,” Medefind said. “You’re literally walking into a fundamental breach of the relationship God intended between parent and child.”

That’s often compounded by tragedy or abuse.

“I remember my biological parents and my two older siblings,” Sandeep said. “My father was an alcoholic, which had a severe impact on our family. He used to be very angry, even abusive.”

He used to take small Sandeep along to hang out with his friends, which troubled his mother, who wanted him to be in school (and who also wanted his father to stop drinking away their small income). Sandeep can remember a final argument, leaving the house with his father, and turning back to see smoke seeping from under the door.

Sandeep’s mother had set herself on fire. He can remember her there, in the tiny home, burning. He and his father smothered the flames in blankets and, with no money for an ambulance, took her in an open-air three-wheeler to the hospital.

“A little child, having to see all that trauma—his mother screaming, going in and out of consciousness, having to carry her with his father—I don’t even know what that did to him,” Vanita said. The experience was so horrendous that Indian relatives, who would normally be interested in adding a boy to their family, rejected him—his karma was terrible.

Vanita had no one to ask about how tragedy might change a child’s brain. “There were no books, no resources, and no counseling available two decades ago. We had no clue how to help this traumatized child. We were struggling to parent him along with our adopted daughter so we just desperately prayed and trusted God.”

In many ways, adoption wades into some of the most profound brokenness in our world.

She was a senior business analyst at pharmaceutical giant Merck, but it quickly became clear she’d need to quit to stay home with Sandeep. He couldn’t follow basic instructions, couldn’t concentrate, and couldn’t function normally. He’d raise his hand in school and then have no answer. He’d stare for hours out a window. He was always angry. He’d lie constantly, even about whether he’d just eaten an orange or not. He even accused Peter and Vanita of kidnapping him.

Medical research shows the brain structure of children who have been abused, neglected, or exposed to trauma can become physically different than their healthy peers. For some who have experienced early trauma, the prefrontal cortex (which does executive functioning and planning) is less developed, their hippocampus (which helps you learn) is smaller, and their amygdala (behavior functioning and survival instincts) shows increased activity.

This shows up in learning disabilities, difficulty focusing, impaired social skills, and trouble sleeping, among a host of other manifestations. Children with altered brains are also more likely to develop PTSD, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and substance abuse disorders.

“When a child saved from abortion or an orphanage is now lying, cheating, stealing, hoarding food, and doing God knows what else, that’s textbook,” adoption consultant Kelly Rosati said. “It’s predictable. The family may have done everything perfectly and still end up in a nightmare.”

The behavior is an outworking of tremendous pain the child has experienced, which both helps a parent to be sympathetic but also sharpens their own grief. Nobody likes to see their baby suffer.

Rosati knows this—three of her four adopted children suffer from mental illness. “While my friends’ kids were in soccer and music, I’m was in meetings with teachers and therapists and psychiatrists and pharmacists,” she said. “I couldn’t drive by a playground for years without bursting into tears because everything I ever dreamt about what it would be like to be a parent turned out to be disastrous. . . . It doesn’t turn out to be a fairy tale.”

But from the outside, it can look like one.

Broken Storytelling

It’s easy to share how God led your family toward adoption. It’s fun to post pictures of sweet babies or cute toddlers on their formal adoption day or “gotcha day” anniversary. But opening up about the disturbing or embarrassing behaviors of your kids can feel like a violation of their privacy. You want to protect your children, and part of that is not wrecking their reputations by telling people all the dark and destructive things they’ve done.

“You love your children and want to be optimistic about their potential to flourish,” said TGC editor Megan Evans Hill, who has adopted twice. “You hope this is just a rough patch, and they’ll come through it soon.”

Sharing probably wouldn’t help anyway—your family or friends without adopted children are unlikely to have any helpful advice to offer.

“One of the obstacles [to getting help] is the inability to do storytelling,” Adopted for Life: The Priority of Adoption for Christian Families and Churches author Russell Moore told TGC. “By necessity, you’re dealing more in abstractions than specifics.”

For example, you may say “unacceptable behavior” instead of “I found her stash of drugs” or “He stole all our credit cards.” But that’s too vague to let other adoptive parents—who may be in a similar situation—know they aren’t alone, or how they can respond.

On one hand, knowing someone else has shared your experiences is a relief and a comfort. “The most helpful thing in the world to me was when I’d say reluctantly to someone, ‘This is what happened,’ and they’d say, ‘Oh yeah. That happened to us too,’” Moore said. “That was worth more than I can ever say.” It’s so powerful that at the Refresh conference for adoptive families, participants hold up signs that say “Same” when the speaker shares an experience they’ve also had.

On the other hand, each child’s background and needs are so unique that even when a parent does open up, it’s difficult to know which advice to follow. “We have two children from the same room in Russia, who have grown up in the exact same environment,” Moore said. “They have completely different personalities and struggles and strengths. You can’t even remotely approach parenting the two of them the same way. How much more for children from different places with different stories.”

This ambiguity—along with the hesitancy of adoptive parents to complain—makes it hard for a church family to find ways to help. While practicing Christians are more than twice as likely to adopt (5 percent) as the average American (2 percent), the vast majority haven’t done it. That means they’re unlikely to anticipate needs—especially as time goes on.

When children are younger, it’s easy for a church family to donate to an adoption fund, bring meals, or babysit. But as the children get older, “you move into much vaguer territory,” Moore said.

How do parents ask for help with children who scream obscenities for hours or cut themselves or run away from home? Especially when you don’t want to give the impression—either to the church or to your own children—that the adoption wasn’t worth it? And how is a church supposed to help?

For churches that want to cultivate a culture of adoption, it’s critical for leaders to find good reading and training on the effects of adoption and childhood trauma, Vanita said. (This is what CAFO plans to help cultivate and supply more of through its center.)

But you don’t need to send everyone to a conference to help adoptive families in your congregation.

“Six years after we adopted our older two kids, our youngest daughter was born,” Vanita said. “She too has been hurt by the effects of trauma. When we look back, I think the biggest needs we had were prayer and encouragement in the Word along with non-judgmental support.”

God’s care for the struggling family flows through the church’s actions, she said. “Remember, adoption is the gospel on display. It is spiritual warfare at its finest. A family that takes in a child is in the thick of the battle with them. The support or neglect from the church can make or break that family.”

Rooted in Jesus

Sandeep refused to eat. He played with fire, even around his baby sister. He beat against his parents’ marriage, trying to turn them against each other. He told Vanita that he hated her, and that she wasn’t his mom, so often over 11 years that she eventually ended up with severe secondary trauma.

At first, “what was hurting me the most was that I couldn’t understand,” Sandeep said. “I kept seeing family members disappear—first my biological mom, then my bio dad, then my bio siblings. I was very confused.” Other things were also confusing—such as moving to a new country, having to live with strangers, living in a house larger than 600 square feet with beds and a washing machine, learning the English language, or being asked to follow a new God who was supposed to be like a loving father.

“I blamed the devastating events of my life on my bio father,” Sandeep said. “So I could not comprehend how God could be considered a good father, especially when he had let my mother die in such a horrific way. And in the middle of that, I also had to accept a new adoptive father. It just didn’t make sense to me.”

“I remember telling him about Jesus and what God has done for us,” Vanita said. “He’d say, ‘Why did God let my mother die without believing in him? If he didn’t want my mom, I don’t want him. I hate God.’”

His anger only increased during the hormonal teen years. Nothing—not Bible studies and faithful church attendance, not constant prayer, not a mission trip to Africa—worked to soften his heart to God or his adopted family. He refused to do his homework, ending up with 350 unfinished assignments toward the end of 9th grade.

“When a child has faced such difficult traumatic situations, most of the brain energy is used to suppress those memories and images,” Vanita said. “I remember him saying it was like a video of his mother dying playing in his mind all the time. He needed to suppress it—and then didn’t have brain energy left for anything else. He was stuck in that moment for years.”

But “God might be working even when we don’t see any progress,” Vanita said. And he was.

When Sandeep was 17, he took his grandparents’ car without permission while they were out. He hadn’t yet learned to drive, and didn’t make it very far before he caught the attention of the police. They let him go, with a strong warning to turn his life around. His parents later made him apologize to his grandparents.

“I was wearing a church camp T-shirt,” Sandeep said. “My grandfather said, ‘How come you’re wearing that shirt and doing all these things? You’re being two-faced.’ The Holy Spirit used that to get to me.”

He went home and told his parents he wanted to surrender and asked the Lord into his heart.

“I was a little skeptical,” Vanita said. After all the years of lying and manipulative behavior, she thought this could be just one more trick. But Peter said “We trust God. This isn’t about Sandeep. Let’s pray with him.”

They did, and the change was almost instant. “From all the years of anger and pain, we saw the beginnings of peace,” Vanita said.

That doesn’t always happen—in fact, “the usual situation is a long slow healing and sanctification,” Rosati said. “Many of the kids we’re talking about who engage in terrible behaviors do already know the Lord. But they haven’t experienced a miraculous healing of the physical harm to their brain, so sanctification and healing and healthier behaviors take much time.”

For Sandeep, too, sanctification took—and is taking—time.

God hates the abuse these kids have endured,” Rosati said. “It’s horrible, and God can still use it in a redemptive way.

“The first thing that really changed was my understanding of life and even why some of these bad things happened in my past,” Sandeep said. “And then I could forgive my bio mom and dad for what occurred, and then I had appreciation for my adoptive mom and dad and the life we now had.”

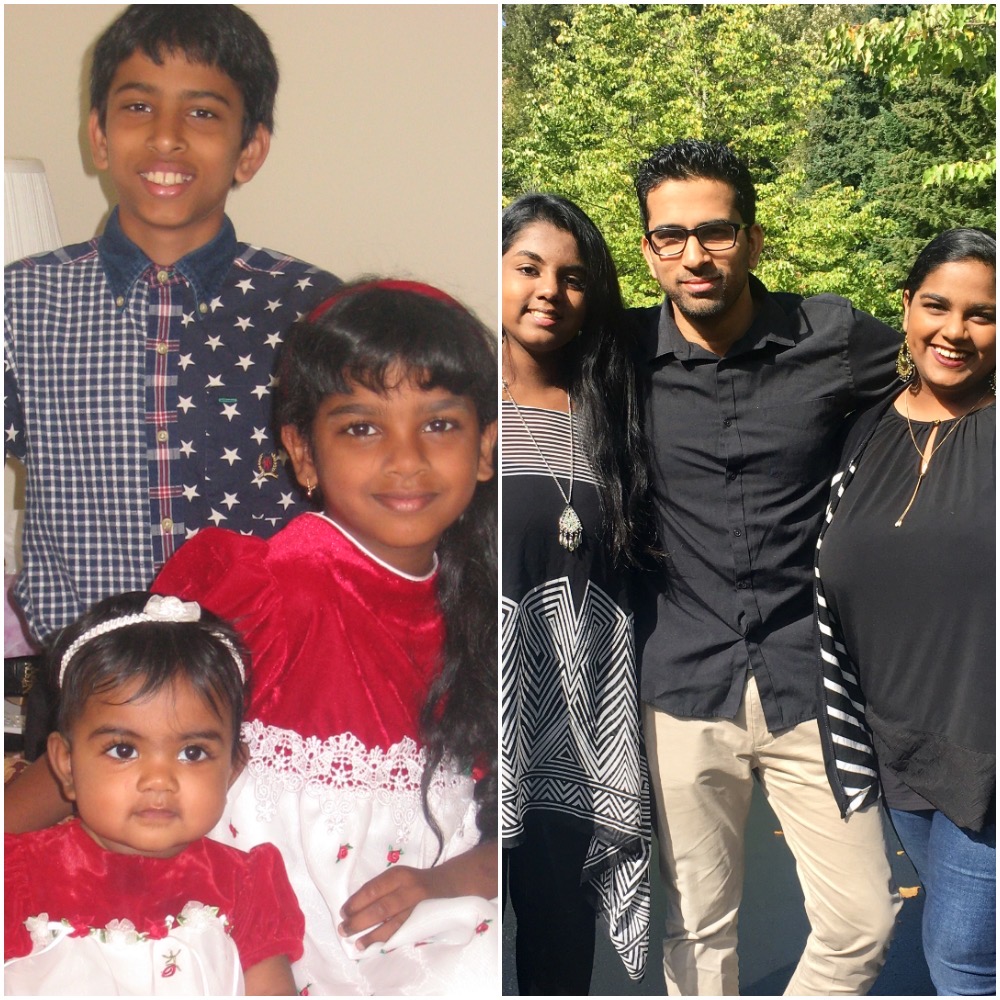

He began to change bad habits, build healthy relationships, and mature in his faith. Today he works as a project manager at an IT company and runs his own business. He willingly shares his story with anyone who is interested—including in India, where he met his wife Shirley.

“I want adoptees to understand that there is a reason things happened to you—God allowed those hurts and pains,” Sandeep said. “It’s not all in vain, like you’re cursed with bad luck. God can use it for a bigger purpose.”

That doesn’t mean God wanted abuse and neglect to happen. “God hates the abuse these kids have endured,” Rosati said. “It’s horrible, and God can still use it in a redemptive way.”

And if you can accept that, then you can reevaluate your life, Sandeep said. “Your gratitude comes when you’re looking at life with a new lens.”

Broken the Right Way

Not every adoption story is as dramatic as Sandeep’s. But stepping into fundamental brokenness is never easy, and adoptive parents often end up feeling broken themselves—physically exhausted, emotionally drained, anxious, angry, confused.

“I’ve seen terrible stories of people who have disrupted their adoptions” by releasing custody of their children, Moore said. “I’ve also seen situations where people have been broken in the right way.”

Rosati is one of them. “It took years to come to a place of homing in on acceptance and gratitude,” she said. “Jesus doesn’t promise things will turn out the way I want them to. He promises his presence. I have to detach my spiritual and emotional well-being from the outcome of my children. My hope for them is in Jesus alone.”

There’s only one way to continue to dig from the well of compassion and love when kids are calling you names or destroying your property, she said. “Only Jesus can give you what you need to stay compassionate and not hate their guts and not hate your life. I’m so amazed by his mercy and patience and kindness—how he just stays and understands. He knows what people do under extreme distress, and he’s here wooing us and loving us back to the only place we can survive, which is in him.”

She’s watched her children attempt suicide, overdose on drugs, and run away. She’s checked them into residential treatment facilities and psychiatric hospitals. But she’s also seen them show the compassion and kindness of Jesus—most recently when they opened their home to a homeless, troubled young man who had nowhere to go.

“I can honestly say I’m grateful,” she said. “I sure would do every bit of it again for my kids. They are completely worth it. My husband and I talk about how, when we’re at the end of our lives, we’ll be so happy that we went this route on this earth.”

Adoption mirrors the gospel story, Medefind said, ‘not only in its beauty, but also in its costliness.’

Adoption mirrors the gospel story, Medefind said, “not only in its beauty, but also in its costliness.” The story that includes redemption and transformation also includes thorns, nails, and a spear in the side.

Adopting is a covenant, but not between parent and child, Vanita said. If that were the case, it would break almost immediately.

“It’s not a commitment to the child, but to the Lord—to do the work however long he wants us to do that for them,” she said. “He has promised that everything will work together for good, even when you don’t see him doing it and may not often see the results on this side of eternity. We press on following in Jesus’ footsteps with the hope of heaven set before us.”

She’s been angry with him. “At times, I have said, ‘I’m done with you, God. We did this to honor you and you have abandoned us.’

“And yet he has not.”

Read More

The Gospel Coalition