Former NFL tight end Benjamin Watson didn’t barge into the pro-life movement like he was sprinting across an entire football field to take out an opposing player one yard from the end zone (though he’s done that).

Instead, his entry was gradual and a little surprising—kind of like a pregnancy itself.

He grew up a preacher’s kid on the East Coast, going to Sunday school and playing football. He was good enough to play for his high-school team, and then for the University of Georgia, and then for the New England Patriots.

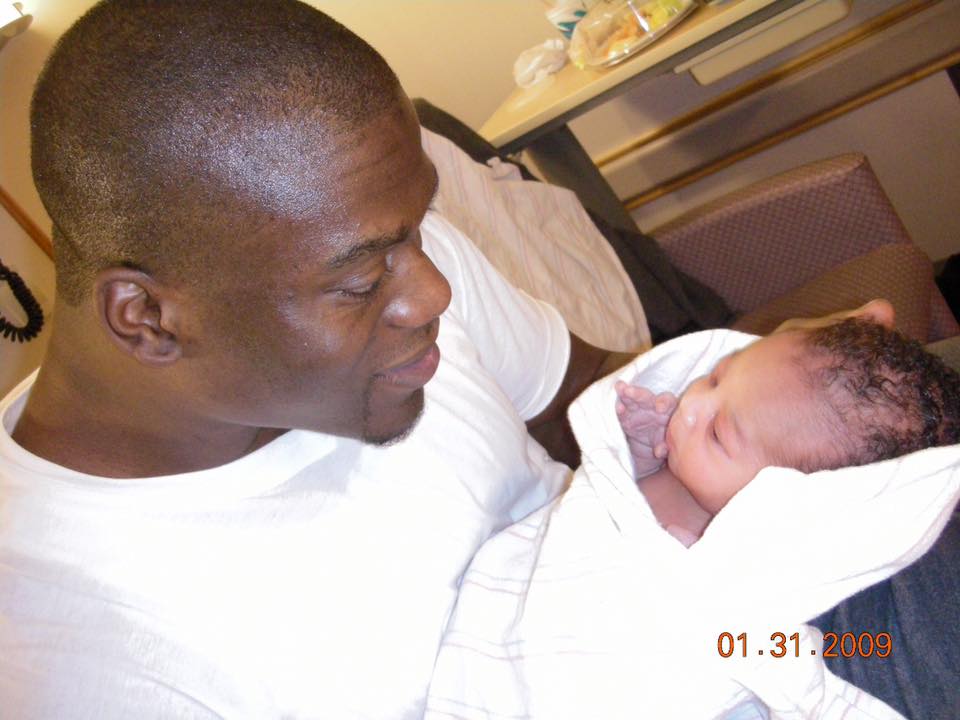

Along the way he met his wife, and they started having babies. They can both remember the first ultrasound of their oldest daughter. When she yawned, Benjamin yawned in response.

“I’d like to provide that service for other pregnant women someday,” his wife, Kirsten, told him as they were walking out. It would be years before they could, but Benjamin remembers this as “the planted seed that would one day, in God’s timing, bring forth fruit.”

In 2018, when Benjamin was playing in Baltimore, the couple donated their first 3D/4D ultrasound machine to a local pregnancy clinic. Later that year, when he moved to the Saints, they donated another in New Orleans.

The previous year, Benjamin spoke at the 2017 March for Life rally in Washington, D.C. He doesn’t know why they asked him––he hadn’t been quiet about his views on abortion, but he hadn’t been outspoken either.

“As tight end for the Baltimore Ravens, Benjamin Watson might not be your typical pro-life leader,” March for Life board chair Patrick Kelly said in his introduction.

He really wasn’t. Benjamin was a professional athlete and father of five, with a busy schedule. And he didn’t have any direct ties to abortion himself—his mom didn’t consider aborting him, he didn’t take any of his girlfriends to get abortions, his wife didn’t have an abortion in her past.

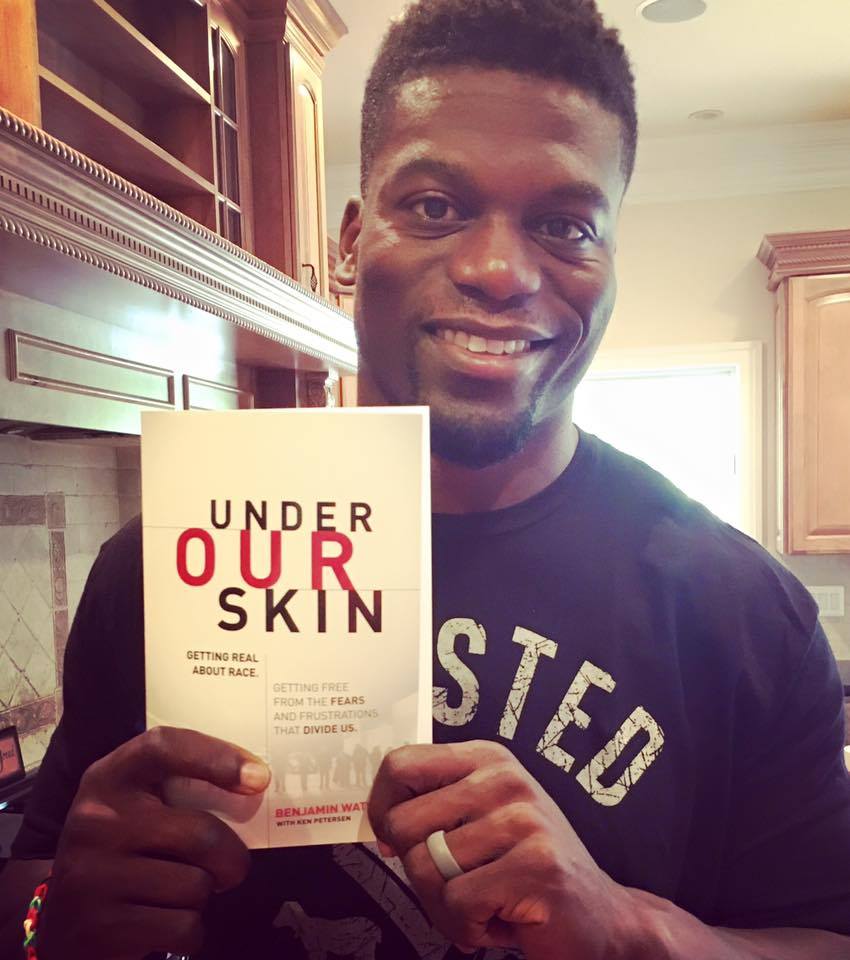

But he is African American, and he does care about racial justice—his Facebook reaction to the Ferguson decision went viral, prompting him to expand it into book titled Under Our Skin: Getting Real About Race.

The Watsons “see a lot of injustice baked into the abortion industry,” Benjamin told TGC. “There’s injustice in both sides—in that proportionally more black children are aborted, and also in that more black women and men, because of racism that leads to disparities in a host of areas, feel it’s their only way out of an unintended pregnancy.”

This fall, he and Kirsten combined the two concerns—pro-life justice and racial justice—in a documentary called Divided Hearts of America.

Too many proponents of pro-life justice ignore racial justice, and too many proponents of racial justice ignore the right to life of unborn children. Ben [Watson] pulls these great causes together better than anyone I know.

“I know many excellent spokespersons for each of those causes, but often the two issues are separated instead of seen as inseparable strands in the same seamless garment of God’s justice,” author and pro-life activist Randy Alcorn wrote. “Too many proponents of pro-life justice ignore racial justice, and too many proponents of racial justice ignore the right to life of unborn children. Ben pulls these great causes together better than anyone I know.”

Growing Up with Football and Jesus

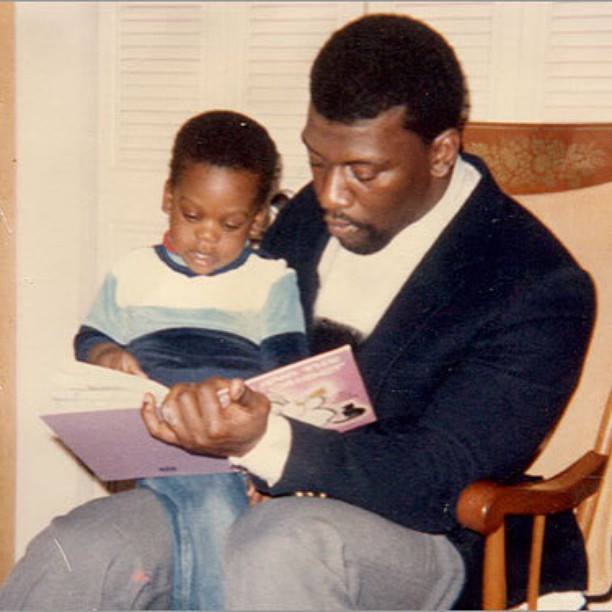

Benjamin is the oldest of six. His parents were both athletic––his dad played football in college, while his mom was a synchronized swimmer. And they both loved Jesus. Before planting his own church, Benjamin’s dad, Ken, was an assistant pastor at two other churches and a speaker at Fellowship of Christian Athletes camps.

Benjamin remembers the night his dad led him to the Lord. They were boxing before bed, and after Ken let 6-year-old Benjamin win, he asked Benjamin if he knew what would happen if he were to die. “He shared a verse I knew––John 3:16—and right then it clicked for me,” Benjamin said. “There is a time in every Christian’s life when the Spirit draws them in a way he hadn’t before. That was the moment for me.”

Though his faith would ebb and flow as he grew, Benjamin wouldn’t ever seriously doubt God or his salvation. Being a Christian is a foundational part of his identity.

So is being African American—both the pride in his heritage and the reality of being different. Early on, a friend at his private grade school told him the cute girl he liked would like him back if he were white. “I was aware that I attended a predominantly white school, but I had never really looked at it that way,” Watson wrote in Under Our Skin. “Now, however, I suddenly could see myself—the blackness of my face and body—in the midst of this sea of white people. I was different from them. And because I was different, I wasn’t good enough.”

He was hearing a similar message from his grandfather, who encouraged him to do whatever he set his mind on, but also cautioned him that because he was black, he’d only make it so far up the totem pole.

When Benjamin was a sophomore in high school, his father moved the family from Virginia to South Carolina so he could plant a church. “I didn’t want to move,” Benjamin said. “But my parents always said that wherever God led them, they would go. So we went.”

Benjamin’s dad planted Rock Hill Bible Fellowship Church, where he still serves. And Benjamin enrolled in the local public high school, where he played football. He watched several of his older teammates go on to play in college and thought, If they can do it, I can do it. And he could.

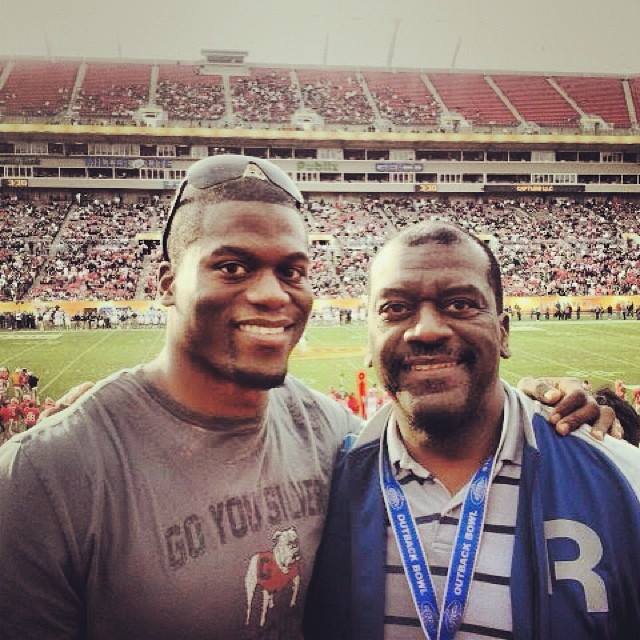

He spent a year at Duke University, then transferred to the University of Georgia to major in finance and play football. While there, he watched the NFL draft some of his friends. If they can do it, I can do it.

And he could. In 2004, Benjamin was a first-round draft pick for the New England Patriots.

Professional Football and Faith

Benjamin was good at his new job. In a profession where the average career length is 3.3 years, he was on the field for 16, playing tight end for four teams. He’d done what he’d set his mind to. He’d made it. And the temptations of money and fame, especially for a recent college grad, were hard to resist.

“Everybody else is having fun, so let me dip my toe in the water and see what it’s like to stay out all night and party or drink or hang out with women,” he said. “I didn’t go all the way—just hung out with my friends and got the feel of it.”

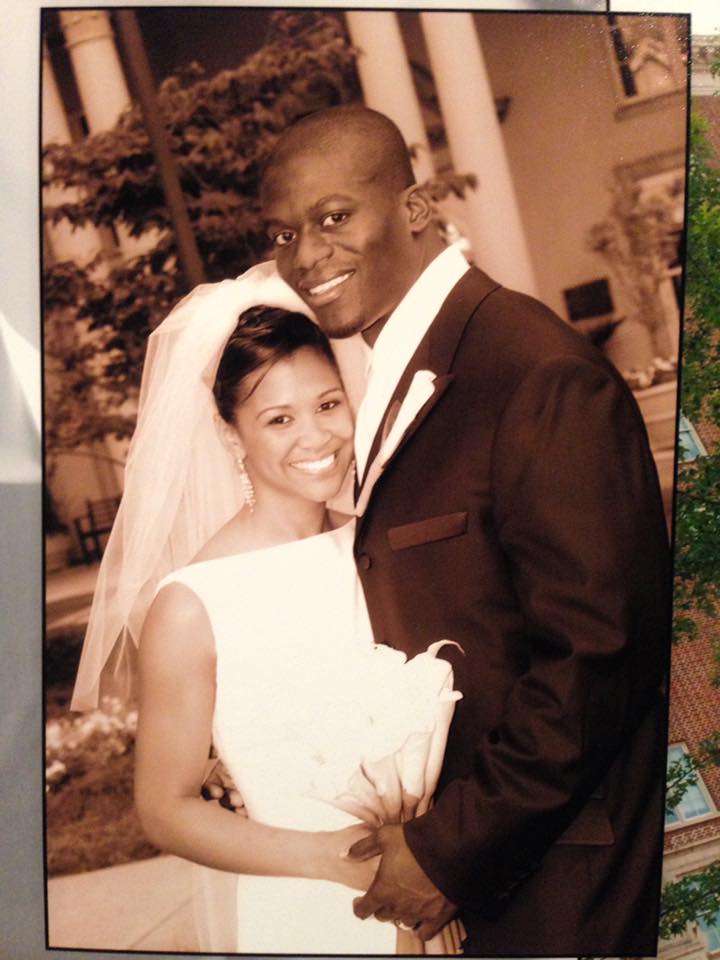

His faith kept him from straying too far, and so did a girl named Kirsten Vaughn he met in college through Fellowship of Christian Athletes. He thought she was beautiful and smart. She was hooked when he answered a leader’s question by explaining that marriage was like a triangle with God at the top.

They got married after his rookie year, then the two type-A personalities argued their way through their first few years of life together. One thing she didn’t love was his job. “She’d get twice as many migraines during football season, thinking about me going onto the field and playing a violent game,” he said.

The two eventually worked out how to disagree in a healthy way, how to show affection effectively, how to handle moving every few years.

One thing they didn’t disagree on was children. Kirsten gave birth to Grace in 2009, months after marveling at her ultrasound. The Watsons followed with Naomi, Isaiah, Judah, Eden, and twins Asher and Levi.

But even though the Watsons had made it to the top of the totem pole, Benjamin’s grandfather wasn’t wrong. Benjamin was still experiencing some racism from teammates. And on the night Kirsten went into labor with Grace, Benjamin carefully drove the speed limit to the hospital––and still got pulled over. The white police officer never did tell him why.

Ferguson

On November 24, 2014, a grand jury declined to indict Darren Wilson, a white police officer, for shooting to death Michael Brown, an unarmed African American teenager who’d stolen cigars from a liquor store.

For some, it felt like a broken criminal justice system protecting itself. Earlier that year, Eric Garner died after a white police officer put him in a prohibited chokehold, Laquan McDonald was shot 16 times while walking away from a white police officer, and 12-year-old Tamir Rice was shot by a white police officer while holding a toy gun at a playground.

Full of emotion, Watson wrote a Facebook reaction that went viral––it was shared 456,000 times and liked more than 840,000 times. Almost exactly a year later, he released a longer version in Under Our Skin.

“Yes, I am pro-life,” he wrote. “And yes, I mean that in its usual sense––that the unborn fetus is a life to be protected. But I mean that in a different and larger way as well. If we are in favor of the unborn life within, should we not also be in favor of the lives of people on the streets, in homes, in churches, and in our neighborhoods?”

Two years later, a friend of a friend was asking if he’d consider speaking at the March for Life.

“Many people wonder why this is important to us,” Watson told the crowd. “The answer is simple—because I, like you, hold life in high esteem.”

He pointed to Jeremiah 9:23 and the lovingkindness, justice, and mercy that delight the heart of God. “My desire is to delight in the very things my Creator does,” he said. Being pro-life isn’t just a political stance or argument, but “from conception to the grave, standing for life includes victims of sex trafficking and abuse, the hungry, the poor, the disadvantaged, as well as the elite.”

The five-minute speech functioned almost like Benjamin’s kickoff into the pro-life space. He and Kirsten donated two ultrasound machines in the next year, and they started getting invitations to speak for organizations such as Live Action, Aid for Women, The Pregnancy Network, and Council for Life.

Meanwhile, the New York State Legislature was passing the Reproductive Health Act, which removed abortion from the criminal code, allows almost any licensed health-care professional to conduct one up to 24 weeks of pregnancy, and lets those providers use “reasonable and good faith professional judgement” when deciding whether to do a late-term abortion.

“It is a sad and evil day when the murder of our most innocent and vulnerable is celebrated with such overwhelming exuberance,” Benjamin tweeted in response to the cheers in the New York State Senate. “We SHOULD be supporting and encouraging the building of families which are fundamental to any society.”

Less than four months later, he joined a rally in New York’s Times Square, encouraging men to take up responsibility for the lives of their children. “Fatherhood begins in the womb,” he told them.

Already, Benjamin working on hosting a pro-life documentary. “It was an opportunity to do something totally different,” he told TGC. “Neither one of us had ever been in film at all. This was another avenue to discover the truth—meaning the history of abortion, from a legal and policy standpoint, and how it affects people in different ways.”

Divided Hearts of America

Abortion is a complex issue, often tangled together with poverty, race, unmarried parents, and an unclear sense of what constitutes “rights.” Most Americans don’t think it should be completely legal (27 percent) or illegal (12 percent), but mostly legal (34 percent) or illegal (26 percent). Opinions vary based on age, level of education, political party, and religious affiliation.

So the Watsons and their crew named the film Divided Hearts of America.

Toward the beginning of the documentary, Benjamin recounts standing on Civil War battlefields with his dad, inspired by those who fought to free the enslaved and wanting to be an abolitionist himself.

“Since then, I’ve been on the front lines of some of the worst human rights violations in today’s world,” Benjamin tells the viewers. And he has, speaking out on issues such as broken criminal justice systems, human trafficking in the Dominican Republic, and the slaughter of Christians in Nigeria.

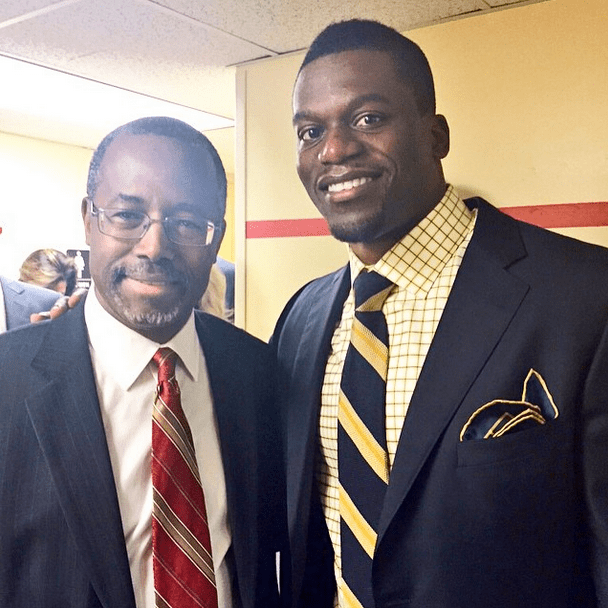

In the documentary, Benjamin homes in on the injustice of abortion. He interviews 30 different people—from pastor and pro-life activist Randy Alcorn to retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson to Martin Luther King Jr.’s niece Alveda King. They draw a pretty clear line—or, rather, multiple lines––connecting racism and abortion.

“As long as you can paint a person as a non-human, as in the days of slavery in America,” King told Benjamin, “they’re not human, so you can do whatever you want to do to them.”

‘As long as you can paint a person as a non-human, as in the days of slavery in America,’ [MLK’s niece] Alveda King told Benjamin, ‘they’re not human, so you can do whatever you want to do to them.’

The film doesn’t pull any punches, pointing out the selective abortion practices of Nazi Germany (Aryan embryos were protected; Jewish ones were not), the eugenics arguments of Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger, and the disproportionately high rates of black babies aborted. (At less than 13 percent of the population, African Americans receive about 27 percent of the nation’s abortions.)

“Initially, you know with the whole abortion issue, I just said, ‘Live and let live,’” Carson told Benjamin. “But the thing that really changed my mind on that is, I was thinking about slavery. And I said, ‘You know, slave owners thought that they owned people, and that they had the right to do anything they want to them, including kill them. What if those others––the abolitionists––had said, “I don’t believe in it, but you can do whatever you want.” Where would we be now?’”

Benjamin also interviewed a former abortionist, women who chose abortion and others who didn’t, a man conceived in rape, and a woman who survived her mother’s abortion attempt. He also talked to New York state senators Liz Krueger and Gustavo Rivera, who support abortion rights.

“It was really eye-opening to hear the conversations,” Kirsten said. “I learned the importance of having a conversation, and of making sure we understand that people who have experienced an abortion are often in the room when we talk about these issues.”

And that’s crucial, because in the black community—where marriage rates are lower, unemployment is higher, and unintended pregnancy is more likely—40 out of every 1,000 reproductive-age women choose an abortion every year. (Compare that to 12 out of every 1,000 white women, and 29 out of every 1,000 Hispanic women.)

“You can’t have an abortion conversation without addressing [that disparity] head on,” Benjamin said. “We need to look at its entire complexity.”

Always Justice

The documentary, which is streaming online, was hailed by some news sources while it was in production, but hasn’t received a lot of attention since it was released in September. That’s not exactly a surprise, since the film isn’t on major streaming platforms such as Netflix or Hulu, and since most mainstream journalists support the right to abortion.

So while The New York Times published Benjamin’s co-authored op-ed on the justice system, CNN talked with him about racial injustice, and an NBC Sports podcaster asked him about the George Floyd riots, hardly anybody is picking up his abortion work.

“Sometimes the things God tells you to do aren’t the most popular,” Kirsten said. (“Please try to show the whole picture instead of being one sided on a topic that you yourself would never have to make a decision like that,” one person tweeted at Benjamin. “Yeah, he’s really a qualified expert,” was another response, along with an eye roll. “[W]ent from a violent sport to promoting violence toward pregnant people. [E]ver thought about ditching violence?” was another.)

“It’s important to stand in truth,” Kirsten said. “The part that hasn’t been favorable, we’ve been able to get through. We’re seeing God’s goodness and graciousness, and having an opportunity to be obedient.”

Divided Hearts has been reviewed by smaller outlets. “I found it extremely unique, engaging, and moving, and I believe you will too,” Randy Alcorn wrote. “I am convinced God will use this film far and wide!”

For the Watsons, who also offer group prices on the film, the biggest hope is that it will spark empathy and conversation.

This documentary isn’t a session to bash people who don’t believe abortion is wrong. The idea is that someone who thinks differently could at least watch and listen and think about what we’re talking about.

“You may know someone who really thinks it is about a woman’s right to make a decision, without thinking about what an abortion actually is,” Kirsten said. “This documentary isn’t a session to bash people who don’t believe abortion is wrong. The idea is that someone who thinks differently could at least watch and listen and think about what we’re talking about.”

Ultimately, for the Watsons, that’s always justice.

“What we talk to our kids about, the verses we memorize as a family—they all center around justice,” Kirsten said. “Whether that is justice about the abortion issue, about human trafficking, or about race—we want to be about the things of God.”

Read More

The Gospel Coalition