In the first week of March last year, John Onwuchekwa and his partners signed a lease on a building. They were starting a coffee shop in their neighborhood, just four blocks from the church Onwuchekwa planted and leads.

It was a dream almost come true—the team had a vision to bring not only good coffee, but also jobs and mentorship opportunities to their underresourced Atlanta neighborhood. And they wanted to celebrate the African heritage of coffee—it was discovered in Ethiopia—with neighbors who are predominately African American.

Portrait Coffee couldn’t have gotten off to a better start. The team set a goal of $30,000 on Kickstarter and raised more than $35,000.

“Then every major coffee media outlet picked it up,” Onwuchekwa said. “We knew we had something special, but we thought it would take time for people to catch on. It didn’t.”

The team found a space in the historic Lottie Watkins building and signed a five-year lease. (In the 1960s, Watkins first African American female real estate broker in the Atlanta market). The unit even had a basement with room for a coffee roaster.

“Then two weeks later COVID hit,” Onwuchekwa said. Schools shut down. Public buildings shut down. Businesses shut down. And restaurants shut down. Georgia Governor Brian Kemp reopened aggressively in April, but the 39 guidelines for restaurants included no self-service drink or condiment stations and no congregating in waiting areas. More than 120 restaurant owners said they wouldn’t open out of fears for public safety.

Since June, Georgia restaurants have been squeezed between Kemp’s push to reopen, the Atlanta mayor’s executive order requiring masks to be worn inside restaurants and other businesses, Kemp’s lawsuit against the mayor, and a federal government letter telling Kemp he’s not in compliance with the White House COVID-19 task force recommendations.

“Few industries have endured more trials and tribulations throughout the health crisis than the restaurant industry,” the Atlanta Eater reported.

Except Portrait Coffee. Even though it never opened its doors, the coffee shop has been profitable since day one.

“Ecclesiastes 11 says sow your seed in the morning and at night—who knows what God is going to do,” Onwuchekwa said. “That’s what we did. . . . The wind blew in all the right ways.”

In a few weeks, Portrait Coffee will finally open its physical location—nearly a year after signing its lease.

“A child in their first year of life doesn’t go through this much change and excitement,” Portrait social media manager Kiyah Crittendon said. “It’s been an incredible year.”

Black Coffee

Onwuchekwa didn’t start drinking coffee until he was an adult.

“We were doing a yearlong discipleship program at the church where I worked,” he said. “To make it work, I got up at 4:30 a.m. on Wednesdays to get there on time.” (Or, if he hadn’t finished preparing, 3:30 a.m.)

The problem was, he was also doing premarital counseling on Tuesday nights, which often lasted until midnight. Wednesdays were so rough that Onwuchekwa’s wife suggested he try some of the Folgers coffee his parents left behind after a recent visit. “I put tons of sugar in it,” he said. “And it wasn’t as bad as I remembered.”

Sow your seed in the morning and at night—who knows what God is going to do.

Onwuchekwa started to walk to a local bakery every day to get a cup of coffee. “I’d put 12 packs of sugar in it just so I could drink it,” he remembers. “But I learned the names of the staff and built friendships there.”

Then he did premarital counseling for folks who worked there. He helped when one had a premature baby. And he started to nerd out on coffee. Whenever he traveled to another city, he’d find a good local place.

“In every shop I saw the same thing—a bunch of people who didn’t look like me,” said Onwuchekwa, who is African American. “I saw the white dude with a hipster beard and tight jeans, and I felt like it was yet another world that I love but where I didn’t fit.”

But by now Onwuchekwa, who doesn’t do anything halfway, was hooked. He read books about the history of coffee—Ethiopian goat herders found it about 1,000 years ago—and how coffee is made and why location makes beans taste differently. When the amount of sugar packets he was consuming became problematic, he went cold turkey and started drinking his coffee black.

“As I started to embrace the bitterness of coffee—not trying to run from it or mask it—I noticed the subtle sweetness,” he said. He loved the way that was a parable for life, and the way it connected him with the black and brown people who grew it in Ethiopia and Uganda and Colombia. And he wanted to share that with his neighbors.

West End

Five years ago, Onwuchekwa planted a church in the West End of Atlanta. It’s a historic neighborhood that suffered from white flight in the ’50s and ’60s, climbed into the middle class, and then sank under the 2008 mortgage crisis. Today the median household income is a little more than $31,000 a year, 60 percent of housing is rental units, and nearly three-quarters of adults haven’t been to college.

“We named our church Cornerstone because we feel like a gospel-preaching church is needed to help restore a community,” Onwuchekwa said. “Whenever you’re rebuilding a structure, the cornerstone is the first you lay, to make sure the rest lines up.”

But you don’t stop with a cornerstone. The church should be building out into the community, concerned with the welfare of those around her, Onwuchekwa said. When this doesn’t happen—like when the broader church didn’t speak against racial segregation or redlining in the 1930s—there are economic consequences. “But where sin abounds,” he said, “grace abounds all the more.”

When Aaron Fender started attending Cornerstone with his girlfriend a few years ago, he and Onwuchekwa hit it off. They both loved basketball, coffee, the West End, and Jesus.

Fender had experience both in the coffee industry and also with start-ups, and soon the two were doodling up a business plan for a coffee shop. “It was very nuts-and-bolts,” Fender said. “Since I’d worked in coffee for so long, I knew what would have to happen for this to be successful.”

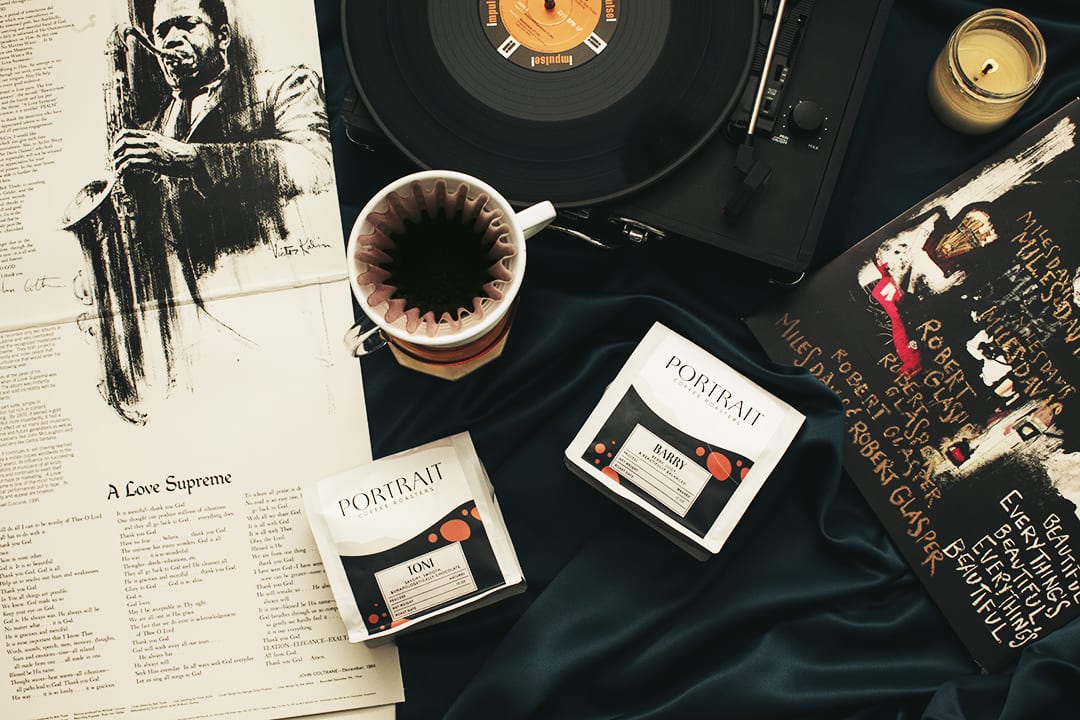

The team—which now included with their wives, Khalid Smith, and Marcus Hollinger—talked about a vision, a budget, and possible locations. They talked about giving their community both the dignity of a good coffee shop and also a place to gather and talk. And they talked about drawing attention to coffee’s African origin, about “reintroducing black coffee.”

They picked the name Portrait Coffee, because “a picture is worth a thousand words, and unfortunately, thousands of words have painted a picture of history that’s photoshopped an entire group of people out,” explained the Kickstarter they tossed up in December. It continued:

Changing the future is about changing’s history’s pictures. Let culture tell it, and the picture that’s painted is that coffee is like golf––it’s a white man’s game, a game where people that look like us are the exception and not the norm. But we want to change that picture.

Their Kickstarter goal for startup costs was $30,000. “We wanted to see if we were actually wanted,” Fender said. “If we failed, then clearly the community wasn’t as interested as we thought. If we succeeded, then we’d know the community wanted us here.”

It was a gamble—the neighborhood only has one coffee shop, if you don’t count McDonald’s, Krispy Kreme, and the gas station. Maybe there was a good reason for that absence. Maybe people in the West End, where one-third live below the poverty level, just couldn’t afford to splurge on coffee.

Ice Age?

Less than a week after launching the Kickstarter, more than 100 people had pledged about $12,000. When the campaign ended a month later, 364 people had pledged more than $35,000.

“We’re blown away by the encouragement of the community,” Fender wrote. A few weeks later, they were signing a lease for a unit in a historic building on the West End’s main drag.

A few days later, a film crew asked if they could sublet the space from Portrait for a little bit. Since it was going to take some time to get the building permits and order a roaster, the Portrait team agreed.

A few days after that, COVID shut everything down. Portrait couldn’t apply for permits or employ contractors, much less think about inviting customers in. They were paying for a space they couldn’t use.

But the film crew also couldn’t finish filming, and they didn’t want to pack up all their equipment. They asked if they could continue to sublet. “We had signed a five-year lease, but we had a tenant in our spot, so not being able to open didn’t cost us anything,” Onwuchekwa said. “God looked out for us.”

Meanwhile, his team was reading Andy Crouch’s warning that COVID wasn’t going to be like a blizzard, or even a winter, but an ice age.

“From today onward, most leaders must recognize that the business they were in no longer exists,” Crouch wrote. “You have to build a fundamentally new deck that reflects the new realities of the community you serve, and the tools that are available to you today.”

The Portrait team knew their community of coffee drinkers could no longer go into a Starbucks on their way to work. And they knew they had a brand-new online store.

“We wanted to fill the gap for people—to help them get better coffee at a cheaper price,” Onwuchekwa said. They started by reaching out to their Kickstarter supporters. They drove their own free, next-day deliveries to any customers in Atlanta. They offered free coffee mugs with orders over $25. And they donated the profits from a limited-edition Tanzanian coffee to emergency assistance for food service workers.

The orders steadily increased. In May, Portrait released blends named after author Toni Morrison and filmmaker Barry Jenkins. (Jenkins ordered some coffee, a mug, and a T-shirt, and gave Portrait a shout-out on Instagram.)

Ten days later, George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis. The Portrait team was devastated and furious.

At work, orders went through the roof.

Scaling Up

“The Black Lives Matter frenzy brought a big leap of growth,” Portrait’s Kiyah Crittendon said.

News media were eager to feature both black-owned businesses and also COVID-era startups, and Portrait was both. Throughout June and July, the company was featured in Atlanta magazine, the Atlanta Journal Constitution, the Atlanta Eater, and the Atlanta Business Chronicle. It showed up on recommended coffee lists by Garden & Gun and HuffPost. And it was featured on Good Morning America.

As social media manager, Crittendon watched Portrait’s Instagram followers jump by about a thousand a week. “We hit 10,000 in July,” she said. “That’s when we started selling out of coffee.”

Throughout March and April, Fender was able to roast beans twice and sell them throughout the week. Now, coffee beans started selling out in a day—sometimes in a morning. Hearth & Hammer General in Illinois put Portrait coffee on its shelves, and so did half a dozen other shops in Atlanta, Chicago, and North Carolina. Big Softie ice cream shop in Atlanta offered Portrait’s Founders roast in its coffee soft serve and its Aunt Viv roast in an iced latte float.

“People were excited to support a black-owned business,” Crittendon said. The quality of the product kept them coming back, Onwuchekwa said.

In September, Portrait joined four other roasters to collaborate on Keurig’s Love blend. In October Google awarded them a $50,000 grant for black-owned start-ups. In November and December, they landed on the best-of or gift-guide lists at Atlanta magazine, Southern Living magazine, and BuzzFeed.

By the end of the year, Portrait was shipping coffee to 800 subscribers in 48 states. The 60 pounds of coffee they were roasting each week in January had ballooned to 800 pounds (sometimes 1,000) a week.

But expanding that much, that fast, isn’t easy.

Price Points

“We’ve had a lot of growing pains,” Fender said. The hours of work, especially during the holiday rush, especially for Fender (who does most of the roasting), were intense. Talks with Trader Joe’s to put Portrait blends on the shelves fell through when the price Trader Joe’s wanted to charge was too low.

And Portrait’s demand has been impossible to keep up with. Until their own space and roaster is ready, they’ve been renting time at a roaster belonging to a nearby coffee shop. Sharing means roasting time is limited, which means supplies are capped.

But the ability to create a God-honoring, financially sustainable workplace has been exhilarating. “This has been more than we ever could have asked,” Crittendon said.

Portrait is careful when choosing import companies, and pays a higher price to coffee growers—between $3 to $5 a pound, compared to industry average $1.10 a pound. That’s so they can ensure both quality beans and a fair wage—not just a fair price, which can be deceiving when the market value of coffee is so low.

Portrait also pays employees—so far two full-time and two part-time––a living wage or more. “In Atlanta, our minimum wage is $7.25,” Fender said. “But in America, $15 an hour is a living wage. That’s a problem.”

The team also wants to be generous, donating or discounting coffee for service projects, community events, or voters standing in line at the polls. But prices have to stay reasonable, especially given Portrait’s location.

Portrait can make the math work because they’re planning to control their own production, Onwuchekwa said. Roasting adds about $6 to a pound of coffee, which is a lot when it’s the difference between a $4 pound of beans or a $10 pound of the same beans, roasted.

“So much success in business depends on a God who gives people the power to make wealth, who directs things,” Onwuchekwa told TGC.

He hopes the physical building, when it opens in the spring, will be “a seed planted in an opportunity desert.” In the West End, “there is no real trajectory for people to do the type of meaningful work within the community that will enable them to purchase a home in the community when the tidal wave of gentrification sweeps over.”

He wants neighborhood kids to see myriad job opportunities in Portrait’s selling and roasting and importing and exporting and technology. He wants regular customers to feel known and cared for. He wants his congregation to be able to use a coffee shop—as he once did—to invest in friendships outside the church.

All of that might even be able to help people process the area’s growing gentrification, which “historically hits communities where people stereotypically aren’t great swimmers,” Onwuchekwa said. In other words, when the economic tide rises, longtime residents sink instead of rising with it. “We want to take our time and teach folks how to swim.”

African Roots

“I know a sandwich or a good cup of coffee doesn’t save anybody,” Onwuchekwa said. “But a church that comes together each week to sing about the amazing generosity of our God should have some of that overflow to the empty stomachs of the people who live in our contexts.”

And customers are “are tasting some of the goodness of what God has done.”

Re-including African Americans in coffee’s history has helped Onwuchekwa to love and embrace the brew, he said. He sees a parallel in Christianity.

“Tim Keller said that most of the time people will stay away from Christianity because they could never see themselves as one,” Onwuchekwa said. “The neighborhood I live in has its share of Hebrew Israelites, Five Percenters, and Black Muslims. They think of Christianity as a white man’s religion. Being an apologist, I have to say, ‘No—y’all think Calvin shaped Christianity, but Calvin’s favorite theologian was Augustine, who came from Africa.’”

The reason Onwuchekwa gets accused of having a white man’s religion and a white man’s drink is that people don’t know the origins, he said. “High-end coffee becomes a parable for me to talk about Christianity.”

Read More

The Gospel Coalition