I woke up on November 1, 1973, a happy 23-year-old within the Communist Party. I had entered the University of Michigan graduate school after reporting for The Boston Globe, along with travel on a Soviet freighter and the Trans-Siberian Railway. A comfortable fellowship let me have my cake and advocate eating the cake of others. Professors complimented me on my Marxist analysis. Free love beckoned.

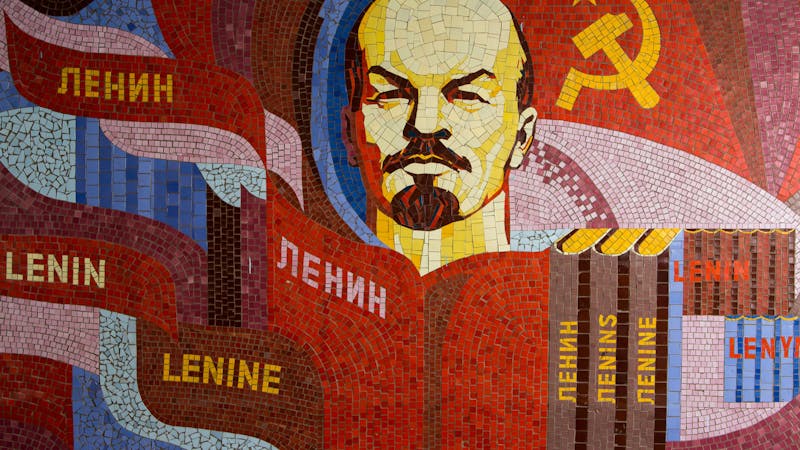

I had just received a visit from two leaders of the Michigan Communist Party. They admired not only my volumes of Marx, Engels, and Lenin, but my three volumes by Bulgarian communist boss Georgi Dimitrov. I told them of my just-approved plan to create, with university funds, a mini-course featuring Soviet scholar Georgy Arkadyevich Arbatov. He had just published in English (translated from Russian) a book with a best-seller title: The War of Ideas in Contemporary International Relations: The Imperialist Doctrine, Methods, and Organization of Foreign Political Propaganda. Great stuff, as I considered it at the time.

Plus, everything was coming up red roses around the world. At a meeting of the Young Workers Liberation League in a University of Michigan seminar room, we heard good reports about the coming North Vietnamese victory over US forces, and progress in key targets for communist activity over the next decade: Afghanistan, Ethiopia, South Africa, and Nicaragua. In Washington, Vice President Spiro Agnew had just resigned in the face of bribery allegations, and Attorney General Elliot Richardson had resigned during the Watergate “Saturday night massacre.”

As an undergraduate at Yale, I had gained exposure to the best and the brightest that “bourgeois culture” could put forward, and found them wanting. Marx and Lenin taught me that the crucial determinant in human history is economic and social class, and I concluded that the bourgeois class had swung and missed: war in Vietnam, poverty at home, corruption in Washington. Time for the working class to take over, under the leadership of the vanguard of the working class, the Communist Party, those willing to do whatever it takes to take over the Capitol and eliminate the betrayers in power.

Frozen in My Chair

At 3 in the afternoon on November 1, I was in my room and sitting in my red chair, rereading Lenin’s famous essay “Socialism and Religion.” In it he wrote, “We must combat religion — this is the ABC of all materialism, and consequently Marxism.” Following Marx, Lenin called religion “opium for the people . . . spiritual booze in which the slaves of capital drown their human image.”

Nothing new. I had abandoned Judaism and declared myself an atheist when I was 14. But suddenly the strangest experience of my life began. Since I had never taken LSD or had a concussion, hallucination, or near-death experience, I can rule out those possible explanations for why I sat in that chair for eight hours, looking at the clock each hour with surprise that I still hadn’t moved.

During those hours, over and over, I saw myself as walking in darkness, but invited to push open a door into a room of brilliant brightness. Meanwhile, questions battered my brain: What if Lenin is wrong? What if God does exist? What is my relationship to this God, if he’s there? Why, when he is kind to me, do I offer evil in return? Why goodness in, garbage out?

Then I started thinking about my journalistic attitudes: Is America really Amerikkka? If not, why am I turning my back on it? Mixing theology and ideology, I started wondering why capitalist desire for money and power is worse than communist desire? Why had I embraced treasonous ideas? Why?

From where were these thoughts emanating? In my brain, Marxism was settled social science. Lenin’s hatred for the “figment of man’s imagination” called “God” was not new to me. It’s hard for me to convey the strangeness, the otherness, of this experience. I have trouble sitting still during lectures. I like to walk while thinking. Yet here I was sitting in the chair, hour after hour, suddenly believing I had done something very wrong by embracing Marx and Lenin.

At 3 in the afternoon, I was an atheist and a communist. When I arose eight hours later, I was not. I had no new data, but suddenly, through some strange intervention, I had a new way of processing data. Over and over, the same beat resonated: I’m wrong. There’s more in heaven and earth than I previously recognized.

Hound of Heaven

It seems mystical, and I can’t even describe well the experience, but it reversed the course of my life.

At 11 that evening, I stood up and spent the next two hours wandering around the cold and dark University of Michigan campus. To borrow an image from nineties basketball, I bounced past the Michigan Union, off the Literature, Science, and Arts building, past Angell Hall, off the Hatcher Graduate Library, nothing but nyet: a firm No to the atheist and Marxist weeds that had grown in me for ten years.

During the next three weeks, I resigned from the Communist Party and read criticisms of the Soviet Union: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Andrei Sakharov, Whittaker Chambers, The God That Failed. I felt I should pursue the question of God’s existence, but disciplined myself to spend the following three weeks writing term papers.

By then the initial glow had faded. I escaped all-encompassing questions by joining the board of the Cinema Guild, a student movie-showing group, and thus gained two free tickets to any of the four or five movies shown on campus each night, with resultant dating opportunities.

But the Holy Spirit wasn’t finished with me. While I ran from reality, God pursued, in a process described by Francis Thompson’s powerful poem “The Hound of Heaven”:

I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways.

God came after me “with unhurrying chase and unperturbed pace.” He turned each of my attempts to escape into new encounters.

Russian Gospel

God came after me. First, I had studied Russian to speak with my Soviet big brothers and had to continue with that to fulfill a PhD language requirement. One night in my room, I picked up the only unread Russian-language work in my bookcase, a New Testament given me as a travel souvenir and retained because it seemed exotic and might be useful for reading practice. With a Russian-English dictionary in front of me, I dived into the Gospel According to Matthew. I was delighted to find chapter 1 easy going: in the second verse Abraham begets Isaac, and other begats lope down the page.

Then came the Christmas story I had never read, followed by a massacre of babies and John the Baptist’s hard-hitting words: “You brood of vipers” (Matthew 3:7). It held my attention, and after a while I didn’t punctuate the verses with sneers. Needing to read slowly and think about the words was helpful. The Sermon on the Mount impressed me. All the Marxists I knew were pro-anger, devoted to fanning proletarian hatred of The Rich. Jesus, though, was not only anti-murder but anti-anger: “Everyone who is angry with his brother will be liable to judgment” (Matthew 5:22). Marxists held to a two-eyes-for-an-eye kind of justice, but Jesus spoke of loving enemies and turning the other cheek.

Reading the Puritans

My next push to faith came in 1974 when, as a graduate student, I had to teach a course in early American literature: it was in the course catalogue, but none of the professors wanted to teach something they saw as dull and reactionary. I had to prepare by reading Puritan sermons, including those of Increase Mather and Jonathan Edwards. Since the Holy Spirit had prepared me, those dead white males made sense to me. Some love Puritan arguments and others hate them, but my childhood prejudice that Christians were stupid people who worshiped Christmas trees faded fast.

The little I knew of Christian thought came largely from my observation of Boston Catholicism, heavy on ritual. The Puritans were different: they believed God is the agent of conversion and regeneration, with humans responsive yet not leading the process. God does not ticket for heaven those with good social conduct: God saves those he chooses to save, regardless of their acts. Salvation then leads to better conduct, sometimes slowly.

That was good news for me. I had broken each of the Ten Commandments, except literally the prohibition of murder (but Jesus called anger a form of murder, Matthew 5:21–22). I certainly was glad that God, if he were anything like the Puritans described him, would not judge me by my works. I assigned to students Thomas Hooker’s sermon on “A True Sight of Sin,” in which Hooker describes our insistence on autonomy: “I will be swayed by mine own will and led by mine own deluded reason.” That was my history, and Hooker seemed to be preaching to me.

Unstoppable Spirit

I was slow. In 1975, instead of visiting a church to find out what flesh-and-blood Christians believe, I started reading about Christianity in the University of Michigan library. I headed down a rabbit trail with Gabriel Marcel and other Christian existentialists, as well as neoorthodox theologians who said they had wedded Christ without much concern for whether the Bridegroom actually existed. I was also in no hurry to leave behind some of the transient pleasures of atheistic immorality.

But I had not left communism merely to believe in pleasant myths or flings. The question was and is truth: as the apostle Paul put it, “If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. . . . If in Christ we have hope in this life only, we are of all people most to be pitied” (1 Corinthians 15:17–19) So, the Holy Spirit worked on me, and in 1976 I finally made a profession of faith. I relished and still love Psalm 73:24–25: “You guide me with your counsel, and afterward you will receive me to glory. Whom have I in heaven but you?”

That sums it up. God offers wisdom now and heaven later — and what good alternative do we have? I had relied on my deluded reason. I was a fanatic who, apart from God’s mysterious intervention, could not be reasoned with. Happily, the Holy Spirit, while not unreasonable, is unstoppable.

![]()

Read More

Desiring God